Living Bridge artist Franz Roubaud. Cooler than in the movies: the case under Icahn and the living bridge - fairy tales of wanderings — LiveJournal

"The campaign of Colonel Karyagin against the Persians in 1805 does not look like a real military history. It looks like a prequel to" 300 Spartans "(40,000 Persians, 500 Russians, gorges, bayonet attacks," This is madness! - No, this is 17- th Jaeger Regiment!"). A golden page of Russian history, combining the slaughter of madness with the highest tactical skill, delightful cunning and stunning Russian impudence. But first things first.

In 1805 Russian empire fought with France as part of the Third Coalition, and fought unsuccessfully. France had Napoleon, and we had the Austrians, whose military glory by that time, it had long since sunk, and the British, who had never had a normal ground army. Both those and others behaved like complete fools, and even the great Kutuzov, with all the power of his genius, could not do anything. In the meantime, in the south of Russia, the Persian Baba Khan, who was reading reports about our European defeats with a purr, had an Ideyka.

Baba Khan stopped purring and again went to Russia, hoping to pay off for the defeats of the previous year, 1804. The moment was chosen extremely well - because of the usual staging of the usual drama "A crowd of so-called allies-krivorukov and Russia, which is again trying to save everyone", Petersburg could not send a single extra soldier to the Caucasus, despite the fact that the entire Caucasus was from 8,000 to 10,000 soldiers.

Therefore, having learned that 40,000 Persian troops under the command of the Crown Prince Abbas-Mirza were heading to the city of Shusha (this is in present-day Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan), where Major Lisanevich was stationed with 6 companies of rangers, Prince Tsitsianov sent all the help he could send. All 493 soldiers and officers with two guns, the hero Karyagin, the hero Kotlyarevsky and the Russian military spirit.

They did not have time to reach Shusha, the Persians intercepted ours on the road, near the Shah-Bulakh River, on June 24. Persian Vanguard. Modest 10,000 people. Not at all at a loss (at that time in the Caucasus, battles with less than a tenfold superiority of the enemy were not considered battles and officially took place in reports as “exercises in conditions close to combat”), Karyagin built an army in a square and all day repelled the fruitless attacks of the Persian cavalry, until only scraps remained of the Persians.

Then he walked another 14 miles and stood in a fortified camp, the so-called wagenburg or, in Russian, walk-city, when the defense line is lined up from carts (given the Caucasian off-road and the lack of a supply network, the troops had to carry significant supplies with them).

The Persians continued their attacks in the evening and fruitlessly stormed the camp until nightfall, after which they took a forced break for clearing piles of Persian bodies, funerals, weeping and writing postcards to the families of the dead. By morning, after reading the manual “The Art of War for Dummies” sent by express mail (“If the enemy is fortified and this enemy is Russian, do not try to attack him head-on, even if you are 40,000, and he is 400”), the Persians began to bombard our walk -city with artillery, trying to prevent our troops from reaching the river and replenishing water supplies. The Russians, in response, made a sortie, made their way to the Persian battery and blew it up, dropping the remnants of the guns into the river.

However, this did not save the situation. Having fought another day, Karyagin began to suspect that he would not be able to kill the entire Persian army. In addition, problems began inside the camp - lieutenant Lisenko and six more traitors defected to the Persians, the next day 19 more joined them - thus, our losses from cowardly pacifists began to exceed those from inept Persian attacks. Thirst, again. Heat. Bullets. And 40,000 Persians around. Uncomfortable.

At the officers' council, two options were proposed: or we all stay here and die, who is in favor? Nobody. Or we are going to break through the Persian encirclement, after which we STORM the nearby fortress, while the Persians are catching up with us, and we are already sitting in the fortress. The only problem is that we are still guarded by tens of thousands.

We decided to break through. At night. Having cut the Persian sentries and trying not to breathe, the Russian participants in the program “Staying alive when you can’t stay alive” almost left the encirclement, but stumbled upon a Persian siding. A chase began, a shootout, then another chase, then ours finally broke away from the Mahmuds in the dark, dark Caucasian forest and went to the fortress, named after the nearby river Shah-Bulakh.

By that moment, a golden aura shone around the remaining participants in the insane marathon “Fight as much as you can” (I remind you that it was already the FOURTH day of uninterrupted fighting, sorties, duels on bayonets and night hide and seek through the forests), so Karyagin simply broke the gates of Shah-Bulakh with a cannonball , after which he wearily asked the small Persian garrison: “Guys, look at us. Do you really want to try? Here, right?"

The boys took the hint and fled. During the run, two khans were killed, the Russians barely had time to repair the gates, as the main Persian forces appeared, worried about the loss of their beloved Russian detachment. But this was not the end. Not even the beginning of the end. After an inventory of the property remaining in the fortress, it turned out that there was no food. And that the convoy with food had to be abandoned during a breakthrough from the encirclement, so there was nothing to eat. At all. At all. At all. Karyagin again went out to the troops:

- Out of 493 people, 175 of us remained, almost all of us are injured, dehydrated, exhausted, in the utmost degree of fatigue. There is no food. There is no wrap. Cores and cartridges are running out. And besides, right in front of our gates sits the heir to the Persian throne, Abbas Mirza, who has already tried several times to take us by storm.

It is he who waits for us to die, hoping that hunger will do what 40,000 Persians could not do. But we won't die. You won't die. I, Colonel Karyagin, forbid you to die. I command you to muster all the impudence that you have, because this night we leave the fortress and break through to ANOTHER FORTRESS, WHICH WE SHOULD TAKE AGAIN, WITH THE ENTIRE PERSIAN ARMY ON THE SHOULDERS.

This is not a Hollywood action movie. This is not an epic. This is Russian history. Put sentries on the walls, who will call to each other all night, creating the feeling that we are in a fortress. We perform as soon as it gets dark enough!

On July 7 at 22 o'clock, Karyagin left the fortress to storm the next, even larger fortress. It is important to understand that by July 7, the detachment had been continuously fighting for the 13th day and was not able to “terminators are coming”, how much “extremely desperate people are moving in the Heart of Darkness of this crazy, impossible, incredible , unthinkable campaign.

With cannons, with carts of the wounded, it was not a walk with backpacks, but a big and heavy movement. Karyagin slipped out of the fortress like a night ghost - and therefore even the soldiers who remained to call to each other on the walls managed to get away from the Persians and catch up with the detachment, although they were already preparing to die, realizing the absolute lethality of their task.

Moving through darkness, darkness, pain, hunger and thirst, a detachment of Russian soldiers encountered a moat through which it was impossible to smuggle cannons, and without cannons, the assault on the next, even better fortified fortress of Mukhrata, had neither meaning nor chance. There was no forest nearby to fill the ditch, and there was no time to look for the forest - the Persians could overtake at any moment. Four Russian soldiers - one of them was Gavrila Sidorov, the names of the rest, unfortunately, I could not find - silently jumped into the ditch. And they lay down. Like logs. No bravado, no talking, nothing. They jumped and lay down. The heavy cannons went straight for them.

Only two climbed out of the ditch. Silently.

On July 8, the detachment entered Kasapet, ate and drank normally for the first time in many days, and moved on, to the Mukhrat fortress. Three miles from it, a detachment of a little more than a hundred people was attacked by several thousand Persian horsemen, who managed to break through to the cannons and capture them. In vain. As one of the officers recalled: “Karyagin shouted: “Guys, go ahead, save the guns!”

Apparently, the soldiers remembered at what cost they got these guns. Red splashed on the carriages, this time Persian, and splashed, and poured, and flooded the carriages, and the ground around the carriages, and carts, and uniforms, and guns, and sabers, and poured, and poured, and poured until the Persians did not flee in panic, failing to break the resistance of hundreds of ours.

Mukhrat was taken easily, and the next day, on July 9, Prince Tsitsianov, having received a report from Karyagin: “We are still alive and for the last three weeks we have been forcing half of the Persian army to chase us. The Persians at the Tertara River ", immediately set out to meet the Persian army with 2300 soldiers and 10 guns. On July 15, Tsitsianov defeated and drove out the Persians, and then joined with the remnants of the detachments of Colonel Karyagin.

Karyagin received a golden sword for this campaign, all officers and soldiers - awards and salaries, silently lay down in the ditch of Gavril Sidorov - a monument at the headquarters of the regiment.

In conclusion, we consider it not superfluous to add that Karyagin began his service as a private in the Butyrsky Infantry Regiment during Turkish war 1773, and the first cases in which he participated were the brilliant victories of Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky. Here, under the impression of these victories, Karyagin for the first time comprehended the great secret of controlling the hearts of people in battle and drew that moral faith in the Russian people and in himself, with which he later never considered his enemies.

When the Butyrsky regiment was moved to the Kuban, Karyagin found himself in the harsh environment of the Caucasian near-linear life, was wounded during the storming of Anapa, and since that time, one might say, has not left the enemy’s fire. In 1803, after the death of General Lazarev, he was appointed chief of the seventeenth regiment, located in Georgia. Here, for the capture of Ganja, he received the Order of St. George of the 4th degree, and the exploits in the Persian campaign of 1805 made his name immortal in the ranks of the Caucasian Corps.

Unfortunately, constant hiking, wounds, and especially fatigue in winter campaign 1806 finally upset the iron health of Karyagin; he fell ill with a fever, which soon developed into a yellow, rotten fever, and on May 7, 1807, the hero died. His last award was the Order of St. Vladimir of the 3rd degree, received by him a few days before his death.

Olga Bartaleva»

Everyone knows the feat of the Greeks at Thermopylae, when their detachment of about 5000 - 6000 people detained the Persian army of 200 - 250 thousand people.

The detachment of Colonel Karyagin numbered 500 people against 20 thousand Persians. That is, the ratio was the same as at Thermopylae.

However, the Greeks of that time were heavily armed and well-organized warriors, superior to the motley and poorly trained troops of the Persians in skill and weapons.

Hoplites on a vase of times Greco-Persian Wars. Armament: spear, short sword, round shield, Corinthian type helmet, bronze shell (cuirass)

The army of Xerxes consisted of representatives of many peoples and tribes subject to the Achaemenid empire. The warriors of each nationality had own weapon and armor. The Persians and Medes, according to the description of Herodotus, wore soft felt hats, trousers and colorful chitons. Armor was assembled from iron scales like fish scales, shields were woven from rods. They were armed with short spears and large bows with reed arrows. On the right thigh was a sword-dagger. Warriors of other tribes were armed much worse, mostly with bows, and often just clubs and burnt stakes, and dressed in copper, leather and even wooden helmets.

Meanwhile, the Russians had two cannons, against several falconet (small cannon caliber 50 - 100 mm) batteries and larger caliber cannons from the Persians.

The Russians held the Persian army not for three days, but for three weeks! In reality, the battle of Thermopylae was a defeat for the Greeks; if they had held the Persians for three weeks, Xerxes' army would have started to starve. And then he would not have captured and plundered a significant part of Greece.

Thanks to the detachment of Colonel Karyagin, the Persians not only did not invade the Caucasus, but in general they were later defeated ... by a detachment of 2400 soldiers, the princes of Tsitsianov!

***

At a time when the glory of the emperor of France Napoleon was growing on the fields of Europe, and the Russian troops fighting against the French were performing new feats for the glory of Russian weapons, on the other side of the world, in the Caucasus, the same Russian soldiers and officers performed no less glorious deeds. One of the golden pages in the history of the Caucasian wars was written by the colonel of the 17th Chasseur Regiment Karyagin and his detachment.

The state of affairs in the Caucasus in 1805 was extremely difficult. The Persian ruler Baba Khan was eager to regain the lost influence of Tehran after the arrival of the Russians in the Caucasus. The impetus for the war was the capture by the troops of Prince Tsitsianov Ganzha. Because of the war with France, St. Petersburg could not increase the strength of the Caucasian Corps; by May 1805, it consisted of about 6,000 infantry and 1,400 cavalry. Moreover, the troops were scattered over a vast territory. Due to illness and poor nutrition, there was a large shortage, so according to the lists in the 17th Jaeger Regiment, there were 991 privates in three battalions, in fact there were 201 people in the ranks.

Having learned about the appearance of large Persian formations, the commander of the Russian troops in the Caucasus, Prince Tsitsianov, ordered Colonel Karyagin to delay the advance of the enemy. On June 18, the detachment set out from Elisavetpol to Shusha, with 493 soldiers and officers and two guns. The detachment included: the patron battalion of the 17th Jaeger Regiment under the command of Major Kotlyarevsky, the company of the Tiflis Musketeer Regiment of Captain Tatarintsov and the artillerymen of Lieutenant Gudim-Levkovich. At that time, Major of the 17th Jaeger Regiment Lisanevich was in Shusha with six companies of rangers, thirty Cossacks and three guns. On July 11, Lisanevich's detachment repulsed several attacks of the Persian troops, and soon an order was received to join the detachment of Colonel Karyagin. But, fearing an uprising of a part of the population and the likelihood of the Persians capturing Shusha, Lisanevich did not do this.

On June 24, the first battle took place with the Persian cavalry (about 3,000) who crossed the Shah-Bulakh River. Several attacks of the enemy who tried to break through the square were repulsed. Having passed 14 versts, the detachment camped at the mound of the Kara-Agach-BaBa tract on the river. Askaran. In the distance one could see the tents of the Persian armada under the command of Pir-Kuli Khan, and this was only the vanguard of the army, commanded by the heir to the Persian throne, Abbas Mirza. On the same day, Karyagin sent a demand to Lisanevich to leave Shusha and go to him, but the latter, due to the difficult situation, could not do this.

At 18.00 the Persians began to storm the Russian camp, the attacks continued with a break until the very night. Having suffered heavy losses, the Persian commander withdrew his detachments to the heights around the camp, and the Persians installed four false batteries to conduct shelling. From the early morning of July 25, the bombardment of our location began. According to the memoirs of one of the participants in the battle: “Our situation was very, very unenviable and became worse from hour to hour. Unbearable heat exhausted our strength, thirst tormented us, and shots from enemy batteries did not stop ... ".

Several times the Persians offered the commander of the detachment to lay down their arms, but they were invariably refused. In order not to lose the only source of water on the night of June 27, a sortie was made by a group under the command of Lieutenant Klyupin and Lieutenant Prince Tumanov. The operation to destroy the enemy batteries was successfully carried out. All four batteries were destroyed, the servants were partly killed, partly fled, and the falconets were thrown into the river. It must be said that by this day 350 people remained in the detachment, and half had wounds. varying degrees gravity.

From the report of Colonel Karyagin to Prince Tsitsianov dated June 26, 1805: "Major Kotlyarevsky was sent by me three times to drive away the enemy who was ahead and occupied elevated places, drove away strong crowds of him with courage. Captain Parfyonov, Captain Klyukin throughout the battle in different occasions were sent by me with rifles and struck the enemy with fearlessness.

At dawn on June 27, the attack on the camp was launched by the approaching main forces of the Persians. The attacks continued throughout the day. At four o'clock in the afternoon there was an incident that forever remained a black spot in glorious history a shelf. Lieutenant Lisenko and six lower ranks ran over to the enemy. Having received information about the plight of the Russians, Abbas Mirza threw his troops into a decisive assault, but having suffered heavy losses, he was forced to abandon further attempts to break the resistance of a desperate handful of people. At night, another 19 soldiers ran across to the Persians. Understanding the gravity of the situation, and the fact that the transition of comrades to the enemy creates unhealthy moods among the soldiers, Colonel Karyagin decides to break through the encirclement, go to the river. Shah Bulakh and occupy a small fortress standing on its shore. The commander of the detachment sent a report to Prince Tsitsianov, in which he wrote: "... in order not to subject the remnant of the detachment to complete and final death and save people and guns, he made a firm decision to break through with courage through the numerous enemy who surrounded on all sides ..."

The conductor in this desperate enterprise was a local resident, an Armenian Melik Vani. Leaving the convoy and burying captured weapons, the detachment moved on to a new campaign. At first they moved in complete silence, then there was a collision with the enemy's cavalry and the Persians rushed to catch up with the detachment. True, even on the march, attempts to destroy this wounded and mortally tired, but still the battle group did not bring good luck to the Persians, moreover, most of the pursuers rushed to rob the empty Russian camp. According to the legends, the Shah-Bulakh castle was built by Shah Nadir, and got its name from the stream flowing nearby. In the castle there was a Persian garrison (150 people) under the command of Emir Khan and Fial Khan, the suburbs occupied enemy posts. Seeing the Russians, the sentries raised the alarm and opened fire. Shots of Russian guns rang out, a well-aimed cannonball smashed the gate, and the Russians broke into the castle. In a report dated June 28, 1805, Karyagin reported: "... the fortress was taken, the enemy was driven out of it and out of the forest with a small loss on our part. On the enemy side, both khans were killed ... Settled in the fortress, I await the orders of your excellency." By evening, there were only 179 people in the ranks, and 45 charges for guns. Upon learning of this, Prince Tsitsianov wrote to Karyagin: "In unheard-of despair, I ask you to back up the soldiers, and I ask God to back you up."

Meanwhile, our heroes suffered from lack of food. The same Melik Vani, whom Popov calls the "Good genius of the detachment", volunteered to get supplies. The most surprising thing is that the brave Armenian did an excellent job with this task, the second operation also bore fruit. But the position of the detachment became more and more difficult, especially since the Persian troops approached the fortification. Abbas Mirza tried to drive the Russians out of the fortification on the move, but his troops suffered losses and were forced to go over to the blockade. Being sure that the Russians were trapped, Abbas-Mirza offered them to lay down their arms, but was refused.

From the report of Colonel Karyagin to Prince Tsitsianov dated June 28, 1805: "Lieutenant Zhudkovsky of the Tiflis Musketeer Regiment, who, despite the wound, volunteered to be a hunter when taking batteries and acted as a brave officer, and Lieutenant Gudim-Levkovich of the 7th Artillery Regiment, who, when almost all his gunners were wounded, he himself loaded the guns and knocked out the gun carriage under the enemy cannon.

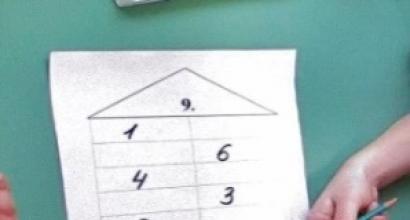

Karyagin decides to take an even more incredible step, to break through the hordes of the enemy to the fortress of Mukhrat, not occupied by the Persians. On July 7, at 22.00, this march began, a deep ravine with steep slopes arose on the way of the detachment. People and horses could overcome it, but the guns? Then Private Gavrila Sidorov jumped down to the bottom of the ditch, followed by a dozen more soldiers. The first gun, like a bird, flew to the other side, the second fell off and the wheel hit Private Sidorov in the temple. Having buried the hero, the detachment continued its march. There are several versions of this episode: "... the detachment continued to move, calmly and unhindered, until the two guns that were with it were stopped by a small ditch. There was no forest to make a bridge nearby; four soldiers volunteered to help the cause, crossing themselves lay down in ditch and guns were transported along them. Two remained alive, and two paid for their heroic self-sacrifice with their lives. "

"Living bridge, an episode from the campaign of Colonel Karyagin to Mukhrat in 1805". Franz Roubaud

On July 8, the detachment came to Ksapet, from here Karyagin sent forward carts with the wounded under the command of Kotlyarevsky, and he himself moved after them. Three versts from Mukhrat, the Persians rushed to the column, but were repulsed by fire and bayonets. One of the officers recalled: "... but as soon as Kotlyarevsky managed to move away from us, we were brutally attacked by several thousand Persians, and their onslaught was so strong and sudden that they managed to capture both of our guns. This is not a thing at all. Karyagin shouted : "Guys, go ahead, save the cannons!" Everyone rushed like lions, and immediately our bayonets opened the way. Trying to cut off the Russians from the fortress, Abbas-Mirza sent a cavalry detachment to capture it, but the Persians failed here too. The disabled team of Kotlyarevsky threw back the Persian horsemen. By evening, Karyagin also came to Mukhrat, according to Bobrovsky, this happened at 12.00.

Having received a report dated July 9, Prince Tsitsianov gathered a detachment of 2371 people with 10 guns and went out to meet Karyagin. On July 15, the detachment of Prince Tsitsianov, having driven back the Persians from the Tertara River, camped near the village of Mardagishti. Upon learning of this, Karyagin leaves Mukhrat at night and goes to connect with his commander.

Having made this amazing march, the detachment of Colonel Karyagin for three weeks attracted the attention of almost 20,000 Persians and did not allow them to go deep into the country. For this campaign, Colonel Karyagin was awarded a golden sword with the inscription "for courage". Pavel Mikhailovich Karyagin has been in the service since April 15, 1773 (Smolensk Coin Company), since September 25, 1775, a sergeant of the Voronezh Infantry Regiment. Since 1783, he was a lieutenant of the Belarusian Jaeger Battalion (1st Battalion of the Caucasian Jaeger Corps). Member of the storming of Anapa June 22, 1791, received the rank of major. Head of defense of Pambak in 1802. Chief of the 17th Jaeger Regiment since May 14, 1803. For the assault on Ganja, he was awarded the Order of St. George, 4th degree.

Late silver medal"For the Persian War" in 1826 - 1828.

Major Kotlyarevsky was awarded the Order of St. Vladimir of the 4th degree, the surviving officers were awarded the Order of St. Anna of the 3rd degree. Avanes Yuzbashi (melik Vani) was not left without a reward, he was promoted to ensign and received 200 silver rubles in a lifetime pension. The feat of private Sidorov in 1892, in the year of the 250th anniversary of the regiment, was immortalized in a monument erected at the headquarters of the Erivans Manglise.

References

1. Popov K. Temple of Glory. T. 1. - Paris, 1931. . - S. 142.

2. Popov K. Decree. op. - P.144.

3. Bobrovsky P.O. The history of the 13th Life Grenadier Erivan Regiment of His Majesty for 250 years. T. 3. - St. Petersburg, 1893. - S. 229.

4. Popov K. Decree Op. - P.146.

5. Viskovatov A. The exploits of the Russians beyond the Caucasus in 1805 // Northern Bee, 1845. - P. 99-101.

6. Library for reading // Life of a Russian nobleman in different eras of his life. T.90. - St. Petersburg, 1848. - P.39.

At a time when the glory of the emperor of France, Napoleon, was growing on the fields of Europe, and the Russian troops fighting against the French were performing new feats for the glory of Russian weapons, on the other side of the world, in the Caucasus, the same Russian soldiers and officers performed no less glorious deeds. One of the golden pages in the history of the Caucasian wars was written by the colonel of the 17th Chasseur Regiment Karyagin and his detachment.

The state of affairs in the Caucasus by 1805 was extremely difficult. The Persian ruler Baba Khan was eager to regain the lost influence of Tehran after the arrival of the Russians in the Caucasus. The impetus for the war was the capture by the troops of Prince Tsitsianov Ganzha.

The moment was chosen extremely well: Petersburg could not send a single extra soldier to the Caucasus. In one of the reports to the emperor, Prince Tsitsianov complained about the lack of troops to fulfill the will of the monarch to capture the Erivan and Baku khanates during the spring and autumn of 1804. In May 1804, Tsitsianov undertook a campaign against the Erivan Khanate, for which Russia competed with Persia. The Persian Khan did not answer and in June 1804 sent a detachment there led by Abbas Mirza. After a series of clashes with the Persians, the assault on Erivan began. The literature describes a number of Russian exploits associated with these events, "the likes of which can only be found in the epic creations of Greece, and in the glorious Caucasian war of the times of Tsitsianov and Kotlyarevsky." For example, it is said about Major Nold, who, with 150 people, defended an earthen redoubt from the attacks of several thousand Persians and managed to defend it. After the arrival of Baba Khan with reinforcements of 15 thousand people, Tsitsianov retreated from Erivan to Georgia in late summer - early autumn, where the riots that had begun, moreover, demanded his presence.

Because of the war with France, St. Petersburg could not increase the strength of the Caucasian Corps; by May 1805, it consisted of about 6,000 infantry and 1,400 cavalry. Moreover, the troops were scattered over a vast territory. Due to illness and poor nutrition, there was a large shortage. So, according to the lists in the 17th Jaeger Regiment, there were 991 privates in three battalions - in fact, there were 201 people in the ranks.

In June 1805, the Persian prince Abbas Mirza launched an attack on Tiflis. In this direction, the Persians had a huge superiority in forces. Georgia faced the threat of a repetition of the massacre of 1795. Shah Baba Khan swore to massacre and exterminate all Russians in Georgia to the last man. The campaign began with the fact that the enemy crossed the Arak at the Khudoperin crossing. The battalion of the 17th Jaeger Regiment, which was covering it, under the command of Major Lisanevich, was unable to hold back the Persians and retreated to Shusha. On the part of Erivan, its actions were limited only by the fact that on June 13 Mehdi Khan of the Qajar brought a three thousandth Persian garrison into the fortress and, having arrested the old ruler Mamed, he himself accepted the title of Erivan Khan.

Upon learning of the appearance of large Persian formations, the commander of the Russian troops in the Caucasus, Prince Tsitsianov, sent all the help that he could send (all 493 soldiers and officers with two guns, Karyagin, Kotlyarevsky (which is a separate story) and the Russian military spirit), ordering Colonel Karyagin stop the advance of the enemy. The strength of both detachments together, if they had managed to unite, did not exceed nine hundred people, but Tsitsianov knew the spirit of the Caucasian troops well, knew their leaders and was calm about the consequences.

The Shusha fortress lay only 80 versts from the Persian border and gave the enemy the opportunity to concentrate significant forces under its cover for action against Georgia. Riots have already begun in Shusha, which broke out, of course, not without the participation of Persian politics, and Lisanevich clearly saw that in the absence of troops, treason could easily open the fortress gates and let the Persians in. And if the Persians occupied Shusha, then Russia would lose the Karabakh Khanate for a long time and would be forced to wage war on its own territory. Tsitsianov himself was aware of this.

So, on June 18, Karyagin's detachment set out from Elisavetpol to Shusha, having 493 soldiers and officers and two guns. The detachment included: the patron battalion of the 17th Jaeger Regiment under the command of Major Kotlyarevsky, the company of the Tiflis Musketeer Regiment of Captain Tatarintsov and the artillerymen of Lieutenant Gudim-Levkovich. At that time, Major of the 17th Jaeger Regiment Lisanevich was in Shusha with six companies of rangers, thirty Cossacks and three guns. On July 11, Lisanevich's detachment repulsed several attacks of the Persian troops, and soon an order was received to join the detachment of Colonel Karyagin. But, fearing an uprising of a part of the population and the likelihood of the Persians capturing Shusha, Lisanevich did not do this. Tsitsianov's fears were justified. The Persians occupied the Askaran castle and cut off Karyagin from Shusha.

On June 24, the first battle took place with the Persian cavalry (about 3,000) who crossed the Shah-Bulakh River. Not at all confused (at that time in the Caucasus, battles with less than a tenfold superiority of the enemy were not considered battles and officially took place in reports as "exercises in conditions close to combat"), Karyagin built an army in a square and continued to go his own way, until the evening repulsing the fruitless attacks of the Persian cavalry. After passing 14 versts, the detachment camped, the so-called wagenburg or, in Russian, walk-city, when the defense line is lined up from carts (given the Caucasian off-road and the lack of a supply network, the troops had to carry significant supplies with them), at the mound (and Tatar cemetery) the Kara-Agach-Baba tract on the river. Askaran. Numerous tombstones and buildings (gyumbet or darbaz) were scattered on the hilly square, representing some protection from shots.

In the distance one could see the tents of the Persian armada under the command of Pir-Kuli Khan, and this was only the vanguard of the army, commanded by the heir to the Persian throne, Abbas Mirza. On the same day, Karyagin sent a demand to Lisanevich to leave Shusha and go to him, but the latter, due to the difficult situation, could not do this.

At 1800, the Persians began to storm the Russian camp, the attacks continued intermittently until the very night, after which they made a forced break for clearing piles of Persian bodies, funerals, crying and writing postcards to the families of the dead. The Persian losses were enormous. There were also losses on the part of the Russians. Karyagin held out at the cemetery, but it cost him one hundred and ninety-seven people, that is, almost half of the detachment. “Ignoring the large number of Persians,” he wrote to Tsitsianov on the same day, “I would have made my way with bayonets to Shusha, but the great number of wounded people whom I have no means to raise makes it impossible for any attempt to move from the place I have occupied.” By morning, the Persian commander withdrew his troops to the heights around the camp.

Military history does not offer many examples where a detachment, surrounded by a hundred times the strongest enemy, would not accept an honorable surrender. But Karyagin did not think to give up. True, at first he counted on help from the Karabakh khan, but soon this hope had to be abandoned: they learned that the khan had betrayed and that his son with the Karabakh cavalry was already in the Persian camp. Several times the Persians offered the commander of the detachment to lay down their arms, but they were invariably refused.

On the third day, June 26, the Persians, wanting to speed up the denouement, diverted water from the besieged and placed four falconet batteries over the river itself, which day and night shelled the walk-city. From that time on, the position of the detachment becomes unbearable, and losses quickly begin to increase. According to the memoirs of one of the participants in the battle: “Our situation was very, very unenviable and was getting worse hour by hour. The unbearable heat exhausted our strength, thirst tormented us, and shots from enemy batteries did not stop ... ". Karyagin himself, already shell-shocked three times in the chest and in the head, was wounded by a bullet through the side. Most of the officers also left the front, and there were not even a hundred and fifty soldiers left fit for battle. If we add to this the torments of thirst, unbearable heat, anxious and sleepless nights, then the formidable persistence with which the soldiers not only irrevocably endured incredible hardships, but still found enough strength in themselves to make sorties and beat the Persians becomes almost incomprehensible.

From the report of Colonel Karyagin to Prince Tsitsianov dated June 26, 1805: “Major Kotlyarevsky was sent by me three times to drive out the enemy who was ahead and occupied elevated places, drove away his strong crowds with courage. Captain Parfyonov, Captain Klyukin throughout the battle on various occasions were sent by me with fittings and hit the enemy with fearlessness.

In order not to lose the only source of water, in one of these sorties on the night of June 27, soldiers, under the command of Lieutenant Ladinsky (according to other information, Lieutenant Klyukin and Lieutenant Prince Tumanov), penetrated even to the Persian camp itself and, having mastered four batteries on Askoran, not only destroyed the batteries and obtained water, but also brought fifteen falconets with them. However, this did not save the situation. It must be said that by this day 350 people remained in the detachment, and half had wounds of varying severity.

The success of this sortie exceeded Karyagin's wildest expectations. He went out to thank the brave rangers, but, finding no words, ended up kissing them all in front of the whole detachment. Unfortunately, Ladinsky, who survived on enemy batteries while performing his daring feat, was seriously wounded by a Persian bullet the next day in his own camp.

For four days a handful of heroes stood face to face with the Persian army, but on the fifth day there was a shortage of ammunition and food. The soldiers ate their last crackers that day, and the officers had long been eating grass and roots. At dawn on June 27, the attack on the camp was launched by the approaching main forces of the Persians. The attacks continued throughout the day. In this extreme, Karyagin decided to send forty people to forage in the nearest villages so that they could get meat, and if possible, bread. At four o'clock in the afternoon there was an incident that forever remained a black spot in the glorious history of the regiment. The foraging team went under the command of an officer who did not inspire much confidence in himself. It was a foreigner of unknown nationality, calling himself the Russian surname Lisenkov (Lysenko); he was the only one of the entire detachment who was apparently weary of his position. Subsequently, from the intercepted correspondence, it turned out that it was indeed a French spy. Lieutenant Lisenko and six lower ranks ran over to the enemy.

By the dawn of the twenty-eighth, only six people from the sent team appeared - with the news that the Persians had attacked them, that the officer was missing, and the rest of the soldiers were hacked to death. Here are some details of the unfortunate expedition, recorded then from the words of the wounded sergeant major Petrov. “As soon as we arrived at the village,” Petrov said, “lieutenant Lisenkov immediately ordered us to pack up our guns, take off our ammunition and walk along the sacks. I reported to him that in the enemy's land it is not good to do this, because, not even the hour, the enemy may come running. But the lieutenant shouted at me and said that we had nothing to fear. I dismissed the people, and myself, as if sensing something unkind, climbed the mound and began to inspect the surroundings. Suddenly I see: the Persian cavalry is galloping ... “Well, I think, it’s bad!” I rushed to the village, and there were already Persians. I began to fight back with a bayonet, but meanwhile I shouted for the soldiers to rescue their guns as soon as possible. Somehow I managed to do it, and, having gathered in a heap, we rushed to make our way. “Well, guys,” I said, “strength breaks straw; run into the bushes, and there, God willing, we’ll also sit out!” - With these words, we rushed in all directions, but only six of us, and then wounded, managed to get to the bush. The Persians poked their nose at us, but we received them in such a way that they soon left us alone.

There are other versions of this event - Lysenko's betrayal. This was an officer who distinguished himself during the assault on Ganzha and in the battle on June 24, 1805, during the reflection of Pir-Kuli Khan, when Karyagin himself recommended him “especially”, just two days before his betrayal. In view of this, it seems more likely to allow Lysenko to be simply careless. It is noteworthy that about future fate Lysenko has no positive information.

Having received information from defectors about the plight of the Russians, Abbas-Mirza threw his troops into a decisive assault, but, having suffered heavy losses, was forced to abandon further attempts to break the resistance of a desperate handful of people.

The fatal failure with foraging made a striking impression on the detachment, which lost here, from a small number of people left after the defense, thirty-five selected fellows at once. At night, another 19 soldiers ran across to the Persians.

But Karyagin's energy did not waver. Having fought another day, Karyagin began to suspect that he would not be able to kill the entire Persian army with 300 Russians. Realizing the gravity of the situation, and the fact that the transition of comrades to the enemy creates unhealthy moods among the soldiers, Colonel Karyagin decides to break through the encirclement, go to the river. Shah Bulakh and occupy a small fortress standing on its shore. The commander of the detachment sent a report to Prince Tsitsianov, in which he wrote: “... in order not to subject the remnant of the detachment to complete and final death and save people and guns, he made a firm decision to break through with courage through the numerous enemy who surrounded from all sides ... ".

The Armenian Yuzbash (melik Vani) undertook to be the guide of the detachment in this desperate enterprise. For Karyagin, in this case, the Russian proverb came true: "Throw bread and salt back, and she will find herself in front." He once did a great favor to one Elizabethan resident, whose son fell in love with Karyagin so much that he was always with him in all campaigns and, as we shall see, played a prominent role in all subsequent events. Another favorable factor was the lack of proper sentry service among the Persian troops, when at night their camp location was never guarded.

Leaving the convoy and burying the captured falconets, praying to God, they loaded the guns with grapeshot, took the wounded onto a stretcher and quietly, without noise, at midnight on the twenty-ninth of June, set out from the camp on a new campaign. Due to the lack of horses, the huntsmen dragged guns on straps. Only three wounded officers rode on horseback: Karyagin, Kotlyarevsky and Lieutenant Ladinsky, and even then because the soldiers themselves did not allow them to dismount, promising to pull out cannons on their hands where necessary. And we will see further how honestly they fulfilled their promise.

At first they moved in complete silence, then there was a collision with the enemy's cavalry and the Persians rushed to catch up with the detachment. True, even on the march, attempts to destroy this wounded and mortally tired, but still battle group, did not bring good luck to the Persians. The impenetrable darkness, the storm, and especially the dexterity of the guide once again saved Karyagin's detachment from the possibility of extermination. Moreover, most of the pursuers rushed to rob the empty Russian camp. By daylight, he was already at the walls of Shah Bulakh, occupied by a small Persian garrison. According to the legends, the Shah-Bulakhbal castle was built by Shah Nadir, and got its name from the stream flowing nearby. In the castle there was a Persian garrison (150 people) under the command of Emir Khan and Fial Khan, the suburbs occupied enemy posts.

Taking advantage of the fact that everyone was still sleeping there, not thinking about the proximity of the Russians, Karyagin fired a volley of guns, broke the iron gates and, rushing to attack, captured the fortress ten minutes later. Its head, Emir Khan, a relative of the Persian crown prince, was killed, and his body remained in the hands of the Russians. The garrison fled. In a report dated June 28, 1805, Karyagin reported: “... the fortress was taken, the enemy was driven out of it and out of the forest with a small loss on our part. On the enemy side, both khans were killed ... Having settled in the fortress, I await the orders of your excellency. By evening, there were only 179 people in the ranks, and 45 charges for guns. Upon learning of this, Prince Tsitsianov wrote to Karyagin: “In unheard-of despair, I ask you to back up the soldiers, and I ask God to back you up.”

The Russians barely had time to repair the gates, as the main Persian forces appeared, worried about the loss of their beloved Russian detachment. Abbas Mirza tried to drive the Russians out of the fortification on the move, but his troops suffered losses and were forced to go over to the blockade. But this was not the end. Not even the beginning of the end. After an inventory of the property remaining in the fortress, it turned out that there was no food. And that the convoy with food had to be abandoned during a breakthrough from the encirclement, so there was nothing to eat. At all. At all. At all. For four days the besieged ate grass and horse meat, but at last these meager supplies were also eaten.

The same melik Vanya, whom Popov calls the "Good genius of the detachment", volunteered to get supplies. The most surprising thing is that the brave Armenian did an excellent job with this task, repeated operations also bore fruit. Several such excursions allowed Karyagin to hold out for another whole week without any particular extremity. But the position of the detachment became more and more difficult. Being sure that the Russians were trapped, Abbas-Mirza offered them to lay down their arms in exchange for great rewards and honors if Karyagin agreed to go into the Persian service and surrender Shah Bulakh, and promising that not the slightest insult would be inflicted on any of the Russians. Karyagin asked for four days for reflection, but so that Abbas-Mirza would feed the Russians with food during all these days. Abbas Mirza agreed, and the Russian detachment, regularly receiving everything they needed from the Persians, rested and recovered.

Meanwhile, the last day of the truce had expired, and by evening Abbas-Mirza sent to ask Karyagin about his decision. “Tomorrow morning, let His Highness occupy Shah-Bulakh,” Karyagin answered. As we shall see, he kept his word. Karyagin decides to take an even more incredible step, to break through the hordes of the enemy to the fortress of Mukhrat, not occupied by the Persians.

It is said that there was once an angel in Heaven who was in charge of monitoring the impossibility. This angel died on July 7 at 10 p.m., when Karyagin set out with a detachment, led by Yuzbash, from the fortress to storm the next, even larger fortress, Mukhrat, which, due to its mountainous location and proximity to Elizavetpol, was more convenient for protection. It is important to understand that by July 7, the detachment had been fighting continuously for the 13th day.

By roundabout roads, through the mountains and slums, the detachment managed to bypass the Persian posts so covertly that the enemy noticed Karyagin's deception only in the morning, when Kotlyarevsky's vanguard, composed exclusively of wounded soldiers and officers, was already in Mukhrat, and Karyagin himself with the rest of the people and with guns he managed to pass dangerous mountain gorges. Even the soldiers who remained to call to each other on the walls managed to get away from the Persians and catch up with the detachment.

If Karyagin and his soldiers were not imbued with a truly heroic spirit, then it seems that local difficulties alone would be enough to make the whole enterprise completely impossible. Here, for example, is one of the episodes of this transition, a fact that stands alone even in the history of the Caucasian army.

On the route of the detachment, a deep ravine or ravine arose (according to the description of Lieutenant Gorshkov, the bed of the Kabartu-chaya river) with steep slopes. People and horses could overcome it, but the guns?

Guys! the battalion leader Sidorov suddenly shouted. Why stand and think? You can’t take the city standing, better listen to what I tell you: our brother has a gun - a lady, and a lady needs help; so let's roll it on guns."

Private Gavrila Sidorov jumped down to the bottom of the ditch, followed by a dozen more soldiers.

There are several versions of this episode: “... the detachment continued to move, calmly and unhindered, until the two guns that were with it were stopped by a small ditch. There was no forest nearby to make a bridge; four soldiers volunteered to help the cause, crossed themselves, lay down in the ditch and carried the guns over them. Two remained alive, and two paid for their heroic self-sacrifice with their lives. In an earlier book, Potto retells the description thus: the guns were stuck into the ground with bayonets like a kind of pile, other guns were laid on them like crossbars, and the soldiers propped them up with their shoulders; the second cannon fell off during the crossing and with all its might hit the head of two soldiers, including Sidorov, with a wheel. The soldier only had time to say: "Farewell, brothers, do not remember dashingly and pray for me a sinner."

No matter how the detachment was in a hurry to retreat, however, the soldiers managed to dig a deep grave, into which the officers lowered the bodies of their dead colleagues in their arms.

On July 8, the detachment came to Ksapet, from here Karyagin sent forward carts with the wounded under the command of Kotlyarevsky, and he himself moved after them. Three versts from Mukhrat, the Persians rushed to the column, but were repulsed by fire and bayonets. One of the officers recalled: “... but as soon as Kotlyarevsky managed to move away from us, we were brutally attacked by several thousand Persians, and their onslaught was so strong and sudden that they managed to capture both of our guns. This is no longer a thing. Karyagin shouted: "Guys, go ahead, save the guns!" Everyone rushed like lions, and immediately our bayonets opened the way. Trying to cut off the Russians from the fortress, Abbas-Mirza sent a cavalry detachment to capture it, but the Persians failed here too. The disabled team of Kotlyarevsky threw back the Persian horsemen. By evening, Karyagin also came to Mukhrat, according to Bobrovsky, this happened at 12.00.

Only now Karyagin sent a letter to Abbas-Mirza in response to his offer to transfer to the Persian service. “In your letter, please say,” Karyagin wrote to him, “that your parent has mercy on me; and I have the honor to notify you that, when fighting with the enemy, they do not seek mercy, except for traitors; and I, who have turned gray under arms, will consider it a happiness to shed my blood in the service of His Imperial Majesty.

In Mukhrat, the detachment enjoyed comparative calm and contentment. And Prince Tsitsianov, having received a report on July 9, gathered a detachment of 2371 people with 10 guns and went out to meet Karyagin. On July 15, the detachment of Prince Tsitsianov, having driven back the Persians from the Tertara River, camped near the village of Mardagishti. Upon learning of this, Karyagin leaves Mukhrat at night and goes to the village of Mazdygert to connect with his commander.

There the commander-in-chief received him with extraordinary military honours. All the troops, dressed in full dress, were lined up in a deployed front, and when the remnants of a brave detachment appeared, Tsitsianov himself ordered: "On guard!" “Hurray!” thundered through the ranks, the drums beat the march, the banners bowed ...

It must be said that as soon as Tsitsianov left Elizavetpol, Abbas-Mirza, counting on the weakness of the garrison left there, broke into the Elizavetpol district and rushed to the city. Although Karyagin was exhausted from the wounds received at Askoran, the sense of duty in him was so strong that, a few days later, the colonel, neglecting his illness, again stood face to face with Abbas Mirza. The rumor that Karyagin was approaching Elizavetpol forced Abbas-Mirza to evade a meeting with the Russian troops. And near Shamkhor, Karyagin, with a detachment not exceeding six hundred bayonets, put the Persians to flight. This is the finale that ended the Persian campaign of 1805. “Fabulous things are happening to you,” Count Rostopchin wrote to Prince Pavel Tsitsianov, “hearing about them, you marvel at them and rejoice that the name of the Russians and Tsitsianov thunders in distant countries ...”

Having made this amazing march, the detachment of Colonel Karyagin for three weeks attracted the attention of almost 20,000 Persians and did not allow them to go deep into the country. Colonel Karyagin's courage bore enormous fruit. Detaining the Persians in Karabagh, it saved Georgia from being flooded by Persian hordes and made it possible for Prince Tsitsianov to gather troops scattered along the borders and open an offensive campaign. And although in February 1806, Prince Tsitsianov was treacherously killed while allegedly handing over the keys to the city of Baku, on the whole, the campaign of 1805 ended with the conquest of the Sheki, Shirvan, Kuban and Karabakh (and in October 1806 and Baku) khanates by Russia.

For his campaign, Colonel Karyagin was awarded a golden sword with the inscription "For Courage". Major Kotlyarevsky was awarded the Order of St. Vladimir of the 4th degree, the surviving officers were awarded the Order of St. Anna of the 3rd degree. Avanes Yuzbashi (melik Vani) was not left without a reward, he was promoted to ensign, received a gold medal and 200 silver rubles in a lifetime pension. The feat of private Sidorov in 1892, in the year of the 250th anniversary of the regiment, was immortalized in a monument erected at the headquarters of the Erivans Manglise.

Continuous campaigns, wounds, and especially fatigue during the winter campaign of 1806 upset Karyagin's health. He fell ill with a fever that turned into yellow rotten fever, and on May 7, 1807, this “gray-haired under arms” hero was gone (excluded from the army lists on July 31, 1807). His last award was the Order of St. Vladimir of the 3rd degree, received a few days before his death. Historian of the Caucasian War V.A. Potto wrote: "Amazed by his heroic deeds, the fighting offspring gave the personality of Karyagin a majestically legendary character, created from him the favorite type in the military epic of the Caucasus."

Finally, the picture of F.A. Roubaud (1856-1928) "Living bridge, an episode from the campaign of Colonel Karyagin to Mukhrat in 1805", created by a battle painter for the Tiflis Museum, which depicts an embellished image of this event of the campaign ("The path was blocked by a deep ravine, to overcome which two cannons in the detachment "They couldn't. There was neither time nor materials for the construction of the bridge. Then Private Gavrila Sidorov, with the words: "The cannon is a soldier's mistress, she needs help," was the first to lie at the bottom of the pit. Ten more people rushed after him. The cannons were transported over the bodies of the soldiers, while Sidorov himself died from a cranial injury."). No wonder, because the painting was painted by the artist in 1892, and was first demonstrated 93 years after the campaign - in 1898. From statements at one military-historical forum: “It is not clear why Roubaud's guns lie on the sidelines, instead of putting and distributing them on top of themselves load. And then you can see how one crazy man generally lay down under the wheels with his stomach up”; “The horses have already been eaten, the cannons were dragged along the mountain paths by the soldiers themselves”; “Roubaud has it amplified for drama, although I think it was enough.”

P.S. Unfortunately, I could not find a portrait of Karyagin, I found a portrait of Kotlyarevsky.

In 1805, the Russian Empire fought with France as part of the Third Coalition, and fought unsuccessfully. France had Napoleon, and we had the Austrians, whose military glory had long since declined by that time, and the British, who had never had a normal ground army. Both of them behaved like complete assholes, and even the great Kutuzov, with all the power of his genius, could not do anything with the idiots from the allies .. Meanwhile, in the south of Russia, the Persian Baba Khan, who was reading reports about our European defeats with a purr, had an Ideyka . Baba Khan stopped purring and again went to Russia, hoping to pay off for the defeats of the previous year, 1804. The moment was chosen very well. Due to problems in Europe, Russia, which again tried to save everyone, could not send a single extra soldier to the Caucasus, despite the fact that there were from 8,000 to 10,000 soldiers in the entire Caucasus. Therefore, having learned that the city of Shusha (this is in present-day Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijan, where Major Lisanevich was located with 6 companies of rangers, 40,000 Persian troops are marching under the command of Crown Prince Abbas-Mirza (I would like to think that he moved on a huge golden platform, with a bunch of freaks, and concubines on gold chains), Prince Tsitsianov sent all the help he could send: all 493 soldiers and officers with two guns, the superhero Karyagin, the superhero Kotlyarevsky (which is a separate story) and the Russian military spirit.

They did not have time to reach Shusha, the Persians intercepted ours on the road, near the Shah-Bulakh River, on June 24. Persian Vanguard. A modest 10,000 people. Not at all confused (at that time in the Caucasus, battles with less than a tenfold superiority of the enemy were not considered battles and officially took place in reports as "exercises in conditions close to combat"), Karyagin built an army in a square and repelled the fruitless attacks of the Persian cavalry all day until the Persians were left with only scraps. Then he walked another 14 miles and stood in a fortified camp, the so-called wagenburg or, in Russian, a walk-city, when the defense line is lined up from wagons (given the Caucasian off-road and the lack of a supply network, the troops had to carry significant supplies with them). The Persians continued their attacks in the evening and fruitlessly stormed the camp until nightfall, after which they took a forced break for clearing piles of Persian bodies, funerals, weeping and writing postcards to the families of the dead. By morning, realizing that if the enemy has fortified and this enemy is Russian, do not try to attack him in the forehead, even if you are 40,000, and he is 400, the Persians began to bombard our walk-city with artillery, trying to prevent our troops from reaching the river and replenish water reserves. The Russians, in response, made a sortie, made their way to the Persian battery and blew it up the fuck, dropping the remnants of the guns into the river, presumably - with malicious obscene inscriptions. However, this did not save the situation. Having fought another day, Karyagin began to suspect that he would not be able to kill the entire Persian army with 300 Russians. In addition, problems began inside the camp - Lieutenant Lisenko and six other assholes defected to the Persians, the next day 19 more blockheads joined them - thus, our losses from cowardly defectors began to exceed those from inept Persian attacks. Thirst, again. Heat. Bullets. And 40,000 Persians around. Uncomfortable.

At the officers' council, two options were proposed: or we all stay here and die, who is in favor? Nobody. Or we are going to break through the Persian encirclement, after which we STORM the nearby fortress, while the Persians are catching up with us, and we are already sitting in the fortress. It 'warm over there. Okay. And flies don't bite. The only problem is that we are no longer even 300 Russian Spartans, but around 200, and there are still tens of thousands of them and they are guarding us. but thinking, there is nothing to do decided to break through. At night. Having cut the Persian sentries and trying not to breathe, the Russian participants in the program "Staying alive when it is impossible to stay alive" almost left the encirclement, but stumbled upon a Persian siding. A chase began, a shootout, then another chase, then ours finally broke away from the Mahmuds in the dark, dark Caucasian forest and went to the fortress, named after the nearby river Shah-Bulakh. By that moment, around the remaining participants in the insane marathon "Fight as much as you can" (I remind you that it was already the FOURTH day of uninterrupted fighting, sorties, duels on bayonets and night hide and seek through the forests) the golden aura of the natural end shone, so Karyagin simply broke the gates of Shah-Bulakh cannonball, after which wearily asked the small Persian garrison: "Guys, look at us. Do you really want to try? Is that true?" The boys took the hint and fled. During the run, two khans were killed, the Russians barely had time to repair the gates, as the main Persian forces appeared, worried about the loss of their beloved Russian detachment. But this was not the end. Not even the beginning of the end. After an inventory of the property remaining in the fortress, it turned out that there was no food. And that the convoy with food had to be abandoned during a breakthrough from the encirclement, so there was nothing to eat. At all. At all. At all. Karyagin again went out to the troops:

- Friends, I know that this is not madness, not Sparta, and in general not something for which human words were invented. Of the already miserable 493 people, 175 of us remained, almost all of us were injured, dehydrated, exhausted, in the utmost degree of fatigue. There is no food. There is no wrap. Cores and cartridges are running out. And besides, right in front of our gates sits the heir to the Persian throne, Abbas Mirza, who has already tried several times to take us by storm. Do you hear the grunting of his tame freaks and the laughter of the concubines? It is he who waits for us to die, hoping that hunger will do what 40,000 Persians could not do. But we won't die. You won't die. I, Colonel Karyagin, forbid you to die. I command you to muster all the impudence that you have, because this night we leave the fortress and break through to ANOTHER FORTRESS, WHICH WE SHOULD TAKE AGAIN, WITH THE ENTIRE PERSIAN ARMY ON THE SHOULDERS. As well as freaks and concubines. This is not a Hollywood action movie. This is not an epic. This is Russian history, chicks, and you are its main characters. Put sentries on the walls, who will call to each other all night, creating the feeling that we are in a fortress. We perform as soon as it gets dark enough!

They say that there was once an angel in Heaven who was responsible for all sorts of impossibilities. On July 7 at 10 pm, when Karyagin left the fortress to storm the next, even larger fortress, this angel died from such impudence. It is important to understand that by July 7, the detachment had been continuously fighting for the 13th day and was in a state of "extremely desperate people, out of anger and fortitude alone, are moving in the Heart of Darkness of this crazy, impossible, incredible, unthinkable campaign." With cannons, with carts of the wounded, it was not a walk with backpacks, but a big and heavy movement. Karyagin slipped out of the fortress like a night ghost, like a bat, like a creature from That Forbidden Side - and therefore even the soldiers who remained to call to each other on the walls managed to get away from the Persians and catch up with the detachment, although they were already preparing to die, realizing the absolute lethality of their task. But the Peak of Madness, Courage and Spirit was yet to come.

Moving through the darkness, haze, pain, hunger and thirst, a detachment of Russian ... soldiers? Ghosts? Saints of war? ran into a moat through which it was impossible to smuggle cannons, and without cannons, the assault on the next, even better fortified fortress of Mukhrata, had neither meaning nor chance. There was no forest nearby to fill the ditch, and there was no time to look for the forest - the Persians could overtake at any moment. Four Russian soldiers - one of them was Gavrila Sidorov, the names of the rest, unfortunately, I could not find - silently jumped into the ditch. And they lay down. Like logs. No bravado, no talking, nothing. They jumped and lay down. The heavy cannons went straight for them. Under the crunch of bones. Barely suppressed moans of pain. More crunch. Dry and loud, like a rifle shot, crackling. Red splashed on the dirty heavy cannon carriage. Russian red.

Only two climbed out of the ditch. Silently.

On July 8, the detachment entered Kasapet, ate and drank normally for the first time in many days, and moved on, to the Mukhrat fortress. Three miles from it, a detachment of a little more than a hundred people was attacked by several thousand Persian horsemen, who managed to break through to the cannons and capture them. In vain. As one of the officers recalled: “Karyagin shouted: “Guys, go ahead, save the guns!” Everyone rushed like lions...". Apparently, the soldiers remembered at what cost they got these guns. Red splashed again on the carriages, this time Persian, and splashed, and poured, and flooded the carriages, and the ground around the carriages, and carts, and uniforms, and guns, and sabers, and poured, and poured, and poured until until the Persians fled in panic, unable to break the resistance of hundreds of ours. Hundreds of Russians. Hundreds of Russians, Russians just like you, who now despise their people, their Russian name, the Russian nation and Russian history, and allowing themselves to silently watch how the state, created by such a feat, such superhuman effort, such pain and such courage, rots and falls apart. Lying down in a moat of apathetic pleasures, so that the cannons of hedonism, entertainment and cowardice go on and on, crushing your fragile shy skulls with their wheels of laughing abomination.

Mukhrat was taken easily, and the next day, on July 9, Prince Tsitsianov, having received a report from Karyagin, we are still alive and for the last three weeks we have been forcing half of the Persian army to chase us, the Persians near the Tertara River, immediately marched towards the Persian army with 2300 soldiers and 10 guns. On July 15, Tsitsianov defeated and drove out the Persians, and then joined with the remnants of the detachments of Colonel Karyagin.

Karyagin received a golden sword for this campaign, all the officers and soldiers - awards and salaries, silently lay down in the ditch of Gavril Sidorov - a monument at the headquarters of the regiment, and we all received a lesson. Ditch lesson. Silence lesson. Crunch lesson. Red lesson. And the next time you are required to do something in the name of Russia and your comrades, and your heart is seized by apathy and a small, ugly fear of a typical child of Russia in the Kali Yuga era, fear of upheavals, struggle, life, death, then remember this moat.

Remember Gabriel.

Egor Prosvirnin, April 2012.

In the picture, something is wrong: a heavy cannon rides through a ravine littered with the bodies of living soldiers, and is about to crush them to death.

Franz Roubaud "Living Bridge" (1898) (clickable)

A popular description of the painting is:

The plot of this work was a real event that occurred during Russo-Persian War 1804-1813 A small detachment of our army of 350 bayonets, the core of which was the chief battalion of the 17th Jaeger Regiment, retreated under the onslaught of the 30,000-strong army of Abbas Mirza. The path was blocked by a deep ravine, which the two cannons in the detachment could not overcome. There was no time or materials for the construction of the bridge. Then Private Gavrila Sidorov, with the words: “The gun is a soldier’s mistress, we must help her,” was the first to lie down at the bottom of the pit. Ten more followed him. The guns were transported over the bodies of the soldiers, while Sidorov himself died from a cranial injury.

What really happened and was it:

Historical context

The picture depicts one of the episodes of the Russian-Persian war of 1805-1813 - the heroic retreat of a small detachment of Colonel Karyagin from a huge Persian army under the command of the 15-year-old heir to the throne Abbas Mirza, which took place in Karabakh in June 1805. How many Persians there were - we do not know, according to Russian sources 20 thousand, which is impossible to believe. In any case, Karyagin's detachment fought boldly against superior enemy forces, did not give up, was able to wait for help, and most of the people escaped.

The war in the Caucasus and Transcaucasia at that time was for the Azerbaijani khanates, which were traditionally vassals of the Qajar shahs. The Russians, who had a well-trained and armed, but small (the main war is going on in Europe, 5 months are left before Austerlitz) army, behaved very aggressively. In the beginning they signed with different owners peace treaties, and then, having gained strength, swallowed them (as it had just happened with the Kartli-Kakheti kingdom). The Persians, whose army was in a shameful state (everything was in a shameful state among the Qajars), acted not by skill, but by numbers - on average they had five times more troops. This led to an unstable balance, and for 7 years, Russian and Persian detachments, with short breaks, drove each other back and forth across the mountains and plains of a relatively small theater of operations, either occupying or leaving various areas. Only in 1813, the Russians tensed up and drove the Persians out forever, and the current Armenia and Azerbaijan were annexed to the empire.

Where did Roubaud get his plot from?

For the first time, the feat of Gavrila Sidorov is mentioned in the book of the long-forgotten writer Dmitry Begichev "The Life of a Russian Nobleman in Different Epochs and Circumstances of His Life" (1851). The book is a kind of mixture of memoirs and patriotic journalism. The story of Gavrila's feat comes from the words of a colonel who was not named by name, a witness to the incident; the narrative is obviously fictionalized.

The most unexpected thing that we see from this story is that the feat is described in a completely different way than it is depicted in the painting by Roubaud. When the cannon is on the edge of a small but insurmountable gully, the quick-witted Gavrila comes up with the idea of building a bridge out of tied guns. Guns stuck into the ground with bayonets become supports, and horizontal guns laid on them serve as beams. Guns are ill-suited for building bridges, and the soldiers support the structure from the edges so that it does not fall apart. The first gun crosses the makeshift bridge safely, the second breaks off, hits Gavrila with a wheel, and he dies from a head injury. All other soldiers remain unharmed.

Then the feat of Gavrila fell into the five-volume "Caucasian War" of the official military historian, Colonel Vasily Potto (1887). This publication can already be considered scientific (Potto apparently worked with military archives), but, alas, it is not provided with the necessary references and is limited to Russian sources (however, no Russian historians can read Persian documents and are not going to this day). The presentation in the book is conducted in an upbeat style and has a hint of semi-official propaganda. It is clear that Roubaud read this particular book in search of suitable plots.

Potto reports that in addition to the story of Begichev, he had access to the report of the native guide, from which it is clear that "four soldiers lay down in a ditch and the cannon drove over them", but the feat is not reflected in the reports of the detachment commander (Potto explains this by Karyagin's great employment). Potto unambiguously joins Begichev's version.

So, we see that Roubaud, to put it mildly, modified the historical source, according to which the soldier died as a result of an accident while crossing a cannon over a bridge cleverly built from improvised means.

Is a live bridge technically possible?

6 pounder field gun early XIX weighed (without limber / charging box) 680 kg. It is possible to assume that from the connected guns supported by people, it will be possible to build some structure that can withstand a point load of 340 kg. From the story it is clear that such a design was not obvious (only one soldier guessed it), and it worked on the verge of an accident. The length of the gun of that era (without a bayonet) was 140-150 cm, and the gun harness without any bridges could overcome obstacles up to 50-60 cm deep (the limit was the size of the wheel, four horses had a traction reserve); therefore, in a given range of obstacle depths, a bridge of guns could be practically suitable.

Meanwhile, the idea of filling a ditch with human bodies seems technically unfeasible. On the canvas, we see eight soldiers in a ditch, the volume of which is (even with loose laying) no more than one cubic meter, that is, with a body length of 1.6 m, 0.6 m2 of the cross section of the ditch. Firstly, a cannon with 130-centimeter wheels could move itself through such a ditch, and secondly, even if the ditch was too steep for a cannon, the 350 soldiers who made up the detachment could throw it with soil or stones in five minutes. And even if we assume that there are no stones nearby and there are no shovels in the detachment, there was clearly at least some property with a total volume of 1 m3 that could fill the ditch - for a start, charging boxes should have been used for this.

The area where the action of the picture unfolds does not correspond at all to the story. Karyagin's detachment moved from Shahbulag (Şahbulaq qalası) to Mukhrat (Kiçik Qarabəy). Both points are connected by a road running along the Shirvan valley; but Mukhrat itself is already in the mountains of the Karabakh range, 300m above the valley. It is doubtful that an ideal road would go up to the mountains, but on the plain there suddenly came across a single ravine through which it was impossible to drag a cannon. It is obvious that the guns were either not transported over the mountainous terrain, or they were accompanied by sappers who had at least shovels, boards, ropes, anchor stakes and bags for carrying soil; otherwise, the soldiers whose bodies could be used to lay obstacles would soon run out. In the memoirs of participants in the Caucasian wars, stopping columns in front of obstacles and calling sappers to overcome them are mentioned incessantly. We can see an example of the excellent work of sappers in the picture of the same Rubo "Storming Akhulgo" (in the comments).

The basis of the moral conflict: a detached wagon and a fat man

The moral conflict contained in the idea of driving a cannon across a ravine and hitting people's bodies becomes clear if we become familiar with two contemporary problems in applied ethics.

Problem A. The unhooked wagon rushes along the tracks. On the main track there are five people who do not notice the car, on the side track there is also a fat man who does not notice the car. You are standing next to the arrow. Would it be ethical to move the car onto a side track, thereby sacrificing one person to save five?

Problem B. The unhooked wagon rushes along the tracks. On the main track there are five people who do not notice the car. You are standing on a bridge over the tracks. A fat man is standing next to you. If you push the fat man off the bridge, the car will brake on him, and five will be saved (if you jump off yourself - no). Is it ethical to push a fat man under a car, thus sacrificing one person to save five?

If you think that you can move the arrow, but you can’t push the fat man off the bridge, you should answer one more question: what is the difference between the two cases, because the consequences are the same in both cases?

Ethics is not mathematics, and there is no single correct answer. An explanation close to me is that in the first case, the car is redirected by means of a switch, and the fat man dies as a person, he himself chose to walk along the railway tracks, an activity that contains a certain probability of being crushed, and this probability was realized for him. In the second case, the fat man dies not as a person, but as an object, as a living brake, but to use a person as an object, cargo, substance, container with biomaterials, etc. is obviously immoral. Including, even if he himself agrees to such use.

For those who have not yet mastered this ethical approach, Task B will help. At the transplant doctor's department, five patients die, who can no longer wait for a donor organ. One needs a liver, another needs a kidney, a third needs a heart, and so on. The saddened doctor goes out into the corridor, and sees a fat man who accidentally wandered into the department. The fat man has perfectly healthy liver, kidneys, lungs ....

Why was this picture painted?

We see that the authors of the middle and second half of the 19th century, who retold (or invented) the story of the exploit of Gavrila Sidorov, by no means represented him as the unfortunate fat man from the above examples. On the contrary, Gavrila's behavior emphasized initiative and ingenuity, combined with a bold willingness to bear reasonable risks. Gavrila acted in their stories as a figure who took responsibility for himself, bypassing the dull officers.

Roubaud rewrote history in a very different way. Soldiers obediently (and even with some joy) go to the slaughterhouse. They give up human dignity and activity, turning themselves into building material, which will now be crushed by the wheels of the gun. Gavrila Sidorov disappears as an individual, and the soldiers merge into an indistinguishable mass. But even Roubaud considered it important to emphasize that the soldiers lay down under the wheels voluntarily - officers who ordered subordinates to sacrifice themselves in this way (that is, pushing a fat man onto the rails) still seemed disgusting to him.

Why did this happen? It seems to me that, as always happens, the artist intuitively caught the spirit of the coming era. Russia, after a long reign of the tsar-peacemaker, began to sharpen its claws again. The aggressiveness of the military command and the government as a whole gradually increased. With whom and why to fight, so far it was not clear, but the desire increased. But the army was no longer the old recruit army, in which the soldiers who served for 25 years considered the company their home, and the endless Caucasian war as a natural way of life. The army became conscription. How will conscripts behave if they have to fight for the Kwantung Peninsula, which the Russian peasant of 1905 did not care about, just as he did not care about the Ganja Khanate in 1805?

And here Roubaud appears on the scene with his sweet lies; Roubaud tells the tsar and the generals what they want to hear - the Russian soldier is immanently devoted to the tsar, thoughtless and heroic, he does not need anything for himself, he is ready to give up human dignity, turn into dust, throw himself under the Juggernaut's chariot for the sake of victory, meaning and benefit which he does not see.

The picture hit the nail on the head and was a great success. It is pleasant for everyone to sit on the chariot of the Juggernaut, under which countless Gabriels throw themselves. Nicholas II, who visited the exhibition at the Historical Museum, bought the painting for his apartments in the Winter Palace. In 1904 began Russo-Japanese War. The wheel rolled and rolled along Gavrily, increasing in size every year. Now it has become known as the Red Wheel. Over the next 50 years, the Wheel moved to Russia more than 30 million Gavrils, their wives and children. In 1918, in the basement of the Ipatiev House, the Wheel also moved the owner of the painting.