Attention psychology. General Psychology Lectures

, november, 1951, Keben-havn, pp. 112-128; J. C. Bouman. ... Stockholm, 1968 (the book contains a detailed exposition and analysis of Rubin's main work in 1915, as well as an extensive bibliography concerning the phenomenon of figure and background). The work published below represents the abstracts of Rubin's report at the IX International Congress of Psychology in Jena (1925). Translation by A.A. Bubbles.^ E. RUBIN. NON-EXISTENCE OF ATTENTION

The concept of attention is characteristic of naive realism. In psychology, it becomes a source of pseudo-problems. For naive realism, attention means a subjective condition or activity that contributes to the experience of objects with high cognitive value, i.e. so that things are experienced as they are, according to the concepts of naive realism, and in reality. Already because of this evaluative point of view, the concept of attention is unsuitable for psychology. However, there is attention explosive and for the most naive realism, since its basic attitude is

144 that subjectivity and appearance coincide. If attention is the designation of the subjective conditions of experience, which are limited, then instead of conducting real research, they turn a blind eye to the main theme of psychology, namely, the disclosure and study of these subjective conditions of experience. And since these conditions, which are partially analyzed in the "psychology of the problem", change from case to case, then attention means, although, as a rule, they do not think about it, either something very vague, or something heterogeneous, in different cases various. Therefore, not a single definition of attention could satisfy psychologists, while outwardly everything could be explained by attention. Therefore, in reality, attention as an explanatory principle had to disappear whenever research penetrated phenomena and revealed their conditions and facts. Since the term attention does not denote anything definite and concrete, in order to nevertheless put it in correspondence with a certain reality, a frivolous assumption brings to life the fiction of the formal and abstract activity of the soul. The word attention is in most cases unnecessary and harmful. When, for example, a certain Mayer looks at his notebook, then pseudoscientific it can be expressed as follows: "Mayer turned his attention to the notebook." Apparently, they say this not only for the sake of sophistication of expression, but also in order to open the way for a dangerous misunderstanding, As if in our cognitive life there is a certain searchlight that moves here and there on the perceived object. Perceived objects are not available, but they seem to be just waiting for attention as a kind of searchlight to highlight them, they arise only with the assistance of all subjective conditions. The so-called types of attention are only descriptive characteristics of the behavior of various people and have no explanatory power. Instead of simply saying that Meyer is unstable, Meyer is said to be of the unstable type of attention. The talk will talk about what kind of experiences and facts are revealed when two voices are simultaneously exposed.

The results will be given in the form concrete examples, in order to show in each individual case how much insufficient and non-speaking is the usual way of explaining attention by work.

145 Koffka Kurt (March 18, 1886 - November 22, 1941) - German psychologist, one of the founders of Gestalt psychology. Was born in Berlin. The initial passion for philosophy (Kant, Nietzsche) was replaced by an interest in experimental psychology... after receiving his doctorate from K. Stumpf (1908), Koffka worked as an assistant to O. Külpe and K. Marbe in Würzburg, then - to F. Schumann in Frankfurt (1910). In Frankfurt, Koffka became close with M. Werth the gamer and W. Koehler, together with whom he began to develop the basic principles of gestalt psychology. In 1911-1924. Koffka - assistant professor at the University of Giessen, since 1927 - professor at Smith College in Northampton (USA). Repeated lecture trips to the United States and England in the early 1920s, and especially Koffka's participation in the International Congress of Psychology at Oxford (1923), were crucial for the spread and acceptance of Gestalt psychology. Koffka was the first Gestalt psychologist to address problems mental development child (1921) and memory (1935). His fundamental (1935), in their completeness and skill of presentation, still remain an unsurpassed collection of achievements of gestalt psychology with a subtle and detailed analysis of its main problems. For many years Koffka was the publisher of the magazine

(\Psychological research>),

Works:. M.-L., 1934; ... In collection: \ Problems of modern psychology>. L., 1925; ... "stalt-Theorie>. ^ ATTENTION

... The clear dismemberment turns out to be a function of the field in the whole and its individual characteristics, and not the result of preexisting anatomical conditions. Of the many other highly indicative experiments, I will mention only one in order to reiterate the proposition that the structure of the field as a whole, and thus the clarity of its parts, is determined not by the placement of stimuli or the factor of attention, but by the actual units generated by organization. If a vertical line made up of strokes (Fig. 13) moves away from the fixation point so far, which is still quite clearly perceived, and the observer then focuses his attention on one of the central parts of this line, then as a result it turns out that this part, instead of being emphasized, is reduced and is now seen unclear. Moreover, if you properly select the ratio of the dimensions of the whole

and its parts, this part may disappear altogether, so that the observer will see a gap in the place where this

line. by isolating part of the structural whole, the observer destroys this part. Here we see irrefutable proof that it is the broader whole as some objective fact that determines the visibility of its parts, and not at all the attitude of the observer (...). A beautiful experiment was performed by Gelb (1921). A double black ring with an outer diameter of 36 cm with a black line thickness of 8 mm and a gap of 5 mm was drawn on a large sheet of cardboard. The subject fixes the center of the ring monocularly. Above, another white ring is superimposed, in which there is a gap of about 12Ї, and the object is removed from the subject so that the two arcs visible through the gap merge into one, completely absorbing the white field separating them. If now the upper ring is removed, then you can clearly see a double whole ring with a white gap between the two black circles. Similarly, if, instead of a double black ring, a single color ring is used, and the object is placed at such a distance from the subject so that through the mask superimposed on top, he "sees the already colorless arc of this colored ring, then when the mask is removed,

147 the subject will again see a quite distinctly colored circle (Fig. 14). The opposite effect is observed when we use double straight lines instead of rings and circles. If, at the same distance as in previous experiments, one of the ends of such a line is fixed, then without a mask, the straight lines will merge at a distance of about 10 cm from the fixation point, while a small segment of them will appear double even at a distance of 20 cm. This shows that the degree of organization of the parts of the field depends on the kind of their organization, on their form.Good forms will also be better figures, that is, they will have a clearer division and color than bad forms. lines gain an advantage over the lines as a whole, arises from the concentration of attention on their small areas.Attention, like an attitude (attitude), is a force that originates in the Ego (Ego) and will therefore be considered by us below. But already from of this experiment, we must draw the conclusion that attention, adding energy to one or another part of the field, will increase its dismemberment, unless it is already dismembered already as much as it is generally possible in this case. Since, in the case of circles, the small parts even lose in comparison with the whole figure, although they should have benefited from the increase in attention to the same extent as the small segments of straight lines, we must admit that inner strength organizations must be more powerful than the effect of the energy that attention adds (...). If the empiricist intends to object to our position that the division of the field into a figure and a background is a matter of organization, then he must first of all explain what it is. Since I know of only one attempt at this kind of explanation, resorting to the hypothesis of attention, the inconsistency of which has been repeatedly revealed, I will refrain from discussing it here (see, for example, Koffka, 1922) (... ). We hear a phone call and rush to the phone or, if we are in a pleasant afternoon nap, we feel the urge to answer the phone and growing anger over such anxiety, even if we do not really obey the call. This peculiar "demand" character of the call is obviously the result of experience; it is also obvious that he appeals to certain of our needs. But all this still does not give us a complete picture of what is happening. In relation to this, as well as on

See the corresponding excerpt from Koffka's work below, p. 149. - Ed.

In relation to many others, we must raise the question of why he was singled out. Trying to answer this question, we find that quite often we choose signals only because they are the most suitable to be signals, because in themselves they already carry a certain "demand character" that allows them to be filled with a specific meaning. The unexpectedness, intensity, and intrusiveness of a telephone call are just such characteristics. Attention. These three characteristics were previously listed as "attentional conditions" along with a number of others that we will only mention: certain qualities, such as bitter taste, musk smell, yellow color, have a particularly strong effect on attention. The dispute about the conditions of attention, which a quarter of a century ago was so intense and played a leading role in the psychological drama, has openly lost all interest for psychologists. The reason for this, as it seems to me, lies not so much in the facts that provided material for this dispute, but in the very concept or concepts of attention that left their imprint on it. We see no benefit in parsing these old notions. Instead, we will define attention according to our general system; at the same time, we will receive such a definition of it, "which is in full accordance with the meaning of e of the word in which it is used in everyday language. When we once faced the fact of attention, we said that it represents a force emanating from the ego and directed to the object.This, of course, is what is usually denoted by the word attention, when, for example, we say: or:. To consider attention (as Titchener, 1910) as simply a quality, attribute or some dimension of dimension) of objects in a field called clarity - means to deprive attention of its main characteristic,

namely, its ego-object interconnectedness. And if we define attention as an ego-object force, then we can consider this to be true in the ratio of not only so-called voluntary, but also involuntary attention. In the first case, the forces come from the Ego; in the second, mainly from the object. This way of looking at attention is naturally not entirely new. He simply did not receive due recognition from those psychologists who wanted to exclude the Ego from their science, and together with the Ego, all psychological dynamics. But when we read the definition of Stout (1909): - we recognize the same general idea. Indeed, we have to assume a certain Ego for stouts-co's.

149 Intensity, surprise, obsession as conditions of attention bring a very definite meaning into our definition. Attention, as a certain force within an integral field, can be awakened not directly by stimulation, but by objects of the field, which, in turn, owe their existence to stimulation. Therefore, we must say that objects that are produced by strong, unexpected and obsessive stimuli, as well as stimuli with special qualities, acquire their own special character due to the fact that they affect the ego. If these old statements about the conditions of attention are true, they again indicate that it may belong not only to the needs of the ego, but also to the objects in the field that are produced by this ego.

LITERATURE

1. Gelb A. Grundfragen der Wahrnehmungs psychologie. Ber. ub. d. VII, Kongr. f. exp. Psych. lena, SS. 114-116.

2.K off k a K. Perception: An Introduction to Gestalt-Theorie.

, 1922, pp. 551-585.

3. Titchener E. B. A Text-Book of Psychology, N. Y "1910.

4. Stout G.F. Analitic Psychology, vol. 1. L., 1909.

150 Kohler Wolfgang (January 21, 1887 - June II, 1967) - German psychologist, one of the founders of Gestalt psychology. He studied at the universities of Tübingen, Bonn and, finally, Berlin, where he studied physics with M. Planck and psychology with K. Stumpf. He received his doctorate in 1909 for his research in the psychology of hearing. In 1910 he was an assistant, and from 1911 he was a private docent in Frankfurt. Decisive for Köhler, as well as for K, Koffka, was the meeting in Frankfurt with M. Wertheimer. Mutual understanding and cooperation of these psychologists laid the foundation for Gestalt psychology. From 1913 to 1920, Kohler was director of the Tenerife Anthropoid Station in the Canary Islands. Here he did his research on the solution problem situations chimpanzees, which led him to the field theory of behavior and to an important concept for gestalt psychology. At the same time, Kehler finishes his composition: (). Brunswick, 1920. Revealing the Existence of Dynamic Self-Regulating physical systems structurally similar to phenomenal gestalts, Koehler develops the so-called principle of isomorphism, which largely determined the nature of his subsequent works, the originality of his position within gestalt psychology. After returning to Germany (1920), Koehler became a professor at Göttingen (1921), and from 1922 to 1935 - director of the Psychological Institute and professor of philosophy and psychology Berlin University... In 1921, together with Wertheimer, Koffka, K. Goldstein and G. Grule Koehler founded the journal

(, came out until 1938), which became the main organ of the gestaltist movement. In 1929, Koehler launched English language his own, in which he gives criticism of behaviorism, introspective and associative psychology. In 1934-1935. at Harvard University, Koehler read the so-called Jam lectures, published in 1938 as a separate book called (). Here Kohler's views on the problems of epistemology are presented in the most rigorous and detailed manner and a comprehensive phenomenological analysis of the concept (requiredness) is given. In 1935 Koehler was forced to leave Germany. From that time until his retirement in 1957, Koehler was professor of philosophy and psychology at Swathmore College (Pennsylvania). In the 1940s, Koehler carried out an important study of the figure aftereffect. In the future, Kohler's interests are concentrated almost exclusively in the field of electrophysiology and electrochemistry of the brain. In 1955-1956. Koehler is a member of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton.

Works:. M., 1930; ...

N.Y. - L., (1929); 3ed. 1959;

... Berlin, 1933; ... N.Y. 1940; ... Bern, 1958; ... Berlin, 1968; ... Berlin, 1971; ... N.Y., 1971.

Literature: W. C. H. Pren-t i with e. , in S. Koch (ed.).

, vol. 1. N.Y., 1959.

Kohler's work included in the anthology

(, vol. 71, No. 3, 1958) made by him together with P. Adams and reflects the nature of his later works. So, a feature of this study is, in particular, Koehler's appeal to the ideas general theory systems, as well as an attempt to establish a close connection between the observed psychological phenomena with electrochemical processes occurring in the brain tissue. Translated by A. A. Bubzyrei

V. Koehler and P. Adame

PERCEPTION and ATTENTION

^

DISTRIBUTION AND ATTENTION

In one of the works devoted to the problem of perceptual organization and learning, we came to the following conclusions.

1. In many situations, learning is no less essential to perceptual dismemberment than a high degree of organization.

2. High degree organization exerts strong pressure on the material, which resists its dismemberment. Such a strong organization should, apparently, overcome the action of learning and hinder it. However, the pressure of a strong organization can be overcome to a certain extent by the subjects.

3. The threshold for dismemberment within a stronger organization should be high. This threshold will probably be lower, but still quite high in the case when the subject perceives the material, having an attitude that facilitates dismemberment.

These conclusions refer to the perceptual phase of learning. As far as we know, so far [only two studies have been carried out that are directly related to the problem we have touched upon: one, earlier, by Krechevsky and the other, not so long ago, by Krech and Kelvin. The results in both cases do not contradict our conclusions.

Starting with Wertheimer's work on perceptual grouping, a special kind of objects have been used to demonstrate the phenomenon of perceptual organization, one of which is shown in Fig. 15. Such an object is generally perceived as a kind of large unit in the shape of a square. When horizontal (or vertical) rows of dots form within this square, they still remain part of this larger organization. Indeed, the fact that in such objects certain rows of spots form horizontal (or vertical) lines is a demonstration of the phenomenon of dismemberment. This was emphasized by Krech and Kelvii, who used such objects in their experiments. These researchers did not measure the threshold for dismemberment of Wertheimer objects, nevertheless, their results show that it should be very high: even when the distances between the spots in one direction were significantly greater than in the other, the subjects often did not notice this at all. despite the multiple presentation of objects. One could argue that this is due to the fact that the time for presenting objects is very short (0.06 sec). This objection is incorrect. The threshold for dismemberment of such objects is just as high when the exposure time is much longer. We have recently shown this in very simple experiments, where objects were presented for one or even a few seconds. To obtain the magnitude of the dismemberment threshold, we changed the ratio of the distances between the spots horizontally and vertically. Some observations were made when the subject considered the object as a background, which meant distracting attention from the object, others when the subject was persistently demanded to refer to the object as such. In the first series of our experiments, we proposed the first task. The objects were composed of black circles ( 1/8 "in diameter), which were attached to a square of white cardboard (7" side). In one direction (vertical or horizontal), the distance between the circles remained constant, namely 13/16 inches. In the other direction, it decreased from 12/16 to 4/16 inches. To protect objects, they were covered with cellophane on top. The contrast between the circles and the background remained almost unchanged.

153 The objects were used as a background for a cardboard figure of a much smaller size, and the subject had to communicate whether he liked the figure or not by moving it in one direction or the other. The figurines did not significantly disturb the perception of objects. Moreover, the objects remained free in front of the subjects all the time while one figure was removed and the next one was presented. Each subject made six consecutive selections. The background object did not change. Four different objects were used in these experiments. Each served as a background in experiments with 5 subjects. The same subject dealt with only one object.

Immediately after six evaluations of the subject, the experimenter removed the object "and asked the subject to describe the background against which the figure was perceived. The results obtained under" under these conditions differed little from each other. It was sometimes reported that the circles were randomly placed; more often, they are organized in vertical or horizontal rows. Finally, in some cases only horizontal or only "vertical organization was noted. Since the actual dismemberment in one direction was accompanied by the suppression of the corresponding relations in the other direction, then only this last case can be considered as an indication" that the dismemberment really happened. In one half of our experiments, the intervals varied vertically, in the other, horizontally. The subjects were students from different colleges. In experiments where the object acted as a background, the results of 20 subjects were as follows. With the constancy of the spacing horizontally or vertically - 12/16 inches and reducing the spacing: vertically or horizontally - up to 7/16, 6/16, 5/16, 4/16 inches, the dismemberment in the vertical direction was noted, respectively, 0,1,2, 4 times, and in the horizontal direction - 0, 0, 1 and 4 times. Since each subject dealt with only one ratio of intervals, these results did not depend on any particular one. The known coincidence of the results in both series indicates that under the conditions of our experiments and for the compared subjects, the upper limit of the dismemberment threshold lies between 5/16 and 4/16 inches. The threshold thus determined turns out to be extremely high. Let's assume that the average threshold is in the 9/32 inch area. In the next series of our experiments, the subjects were presented with objects of the same type with instructions to describe each of them immediately "after presentation. Now the object no longer acted as a background of perception, but was directly directed at it. We did not even try to introduce any special setting besides this simple requirement of attention to the object.

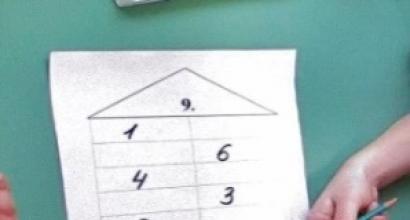

154 10 students participated in the experiments. Each of them was sequentially presented with the entire set of objects, "starting with those where the horizontal and vertical gaps were equal" to each other (12/16 "). Objects in which the gaps were shortened either horizontally or vertically were presented alternately. All objects were presented for 1 second.Since it turned out that dismemberment both vertically and horizontally occurs at the same ratio of intervals, the results for these two situations are here combined, For 10 subjects, they were as follows:

Gap reduction limit

(inches) 12/16 10/16 9/16 8/16 7/16 6/16 5/16 Dismemberment cases. ... ... 0 0 1 2 8 9 10

We can say that for the group as a whole, the threshold was now in the interval between 8/16 and 7/16 inches, that is, with the difference in distance (horizontally and vertically), noticeably less than in the case when the object protruded into as background. Assuming it to be 15/32 inches, we "get about 37% of the largest spacing for it. Therefore, a setting that requires attention to an object lowers the threshold, even though it is still high enough. Dismemberment is rarely seen as long as the spacing is in one direction will not decrease by more than one third. Since it may seem that the exposure of 1 sec is still too short for dismemberment to occur easily, the experiments were repeated with an exposure of 3 sec. Again there were 10 subjects. The results were as follows. :

Gap reduction limit

(inches) 12/16 10/16 9/16 8/16 7/16 6/16 5/16 Number of dismemberments. ,. 0 0 0 2 8 9 10

It is difficult to see any difference between these results and those obtained at shorter exposures. Therefore, one can trust the results of Krech and Calvin. Kretsch and Calvin showed that the ease with which dismemberment is performed by different people is not related to visual acuity. The threshold value in our group can be considered as another confirmation of this fact. None of the twenty subjects showed dismemberment when the bi-directional distances were 12/16 and 10/16 inches, respectively.

155 that is, when the difference approached 1/8 of an inch. As such, most subjects were able to compare distances with greater accuracy. In this regard, we found a very simple and expressive fact. If we place one of our objects in front of us, which, despite the significant difference between vertical and horizontal gaps, still does not seem to us to be dismembered, then it is easy to distinguish three circles that together form right triangle, and detach from the surrounding circles. The sharp difference between the vertical and horizontal sides of a triangle is quite obvious under these conditions. in the sequence in which the objects were presented, the next decrease in the gaps between the circles could occur both vertically and horizontally. The results do not allow us to say that the dismemberment was more easily carried out horizontally, although one would think that the vertical-horizontal "illusion would act in this direction. Obviously, this did not have a noticeable effect on the results of our experiments. The illusion did appear, however when a right-angled triangle stood out. In this case, although objectively the intervals were equal, the vertical gap seemed noticeably large. Note that while "vertical (or horizontal lines are formed in our objects with great difficulty, these the objects themselves contain components that are perceived as such "all the time, namely spots or circles. The conditions for storing them as independent entities, of course, are so favorable that they "almost do not show the inclusion in the general structure of an object or, under certain conditions of dismemberment, in vertical or horizontal lines. The sequence in which" objects were presented in the case when they were paid attention to a certain attitude favorable to an undivided organization. The threshold obtained under these conditions could be higher than under other conditions. If this is so, then the results of our experiments do not show the dismembering effect of attention in all its fullness, however, in our situation, such an increase in the threshold could hardly have been any large. When we ourselves considered an object that was perceived by only a few as dismembered, it did not seem dismembered at all to us, and only after persistent efforts to introduce

156 strong> dismemberment sometimes there was a very unstable dismemberment of individual areas of the object. While agreeing with the results of Krech and Calvin, we cannot agree with some remarks about Gestalt psychology. First, it can be argued that both their own observations and ours hardly mean that under certain conditions the principles of Gestalt psychology do not work. Of course, Gestalt psychologists have never insisted that proximity is always the determining factor, even when the forces of the organization acting in a different direction are extremely strong. Is it an objection to the law of attraction that an airplane can take off from the ground and soar for hours; in the air? Second, on the basis of their data, these authors object to the proposition that proximity effects are perceived. When Gestalt psychologists made "this assumption many years ago, they used the term to object to the notion that organization is simply the result of learning, which gradually transforms so-called sensations into objects or groups. This term does not at all deny that organizations it takes a certain time (very short) to complete its work.On the contrary, certain phenomena, such as the y-motion, have always been considered as indications of this fact.In this regard, it remains to be noted that these authors only privately confirmed The fact is that even simple perceptual structures are the product of some rapidly flowing development, which is directed from more homogeneous to more and more dissected. Gesh-talt psychologists are quite familiar with this idea. Indeed, in the work of Wertheus, "a measure, where questions of perceptual grouping were considered, this position was clearly expressed many years ago. The tendency of a larger organization to prevent the emergence of more fractional structures is not limited to the case of objects consisting of many spots. In subsequent experiments we used objects of a different genus, which Wertheimer also proposed at one time.Letters and words as independent units with their familiar characteristics can disappear when their mirror image is added to them.Only a few people, perceiving this object, involuntarily realize the fact that the upper part of the object represents a word (man) In disguises of this type, the leading one is the tendency of the organization to form closed figures, which change some characteristics of the parts so much that involuntarily they can no longer be recognized. For example, when our object is perceived as a whole, then the outline of a word and its mirror image form a coherent area that acquires the character of a figure (which was once described by Rubin). When every word

157 is perceived separately, the outline of a word is a simple graphic figure, however, within a larger object, the word and its letters tend to lose their familiar characteristics and are rarely involuntarily recognized. The principle involved here in action is different from that which is valid in the case of Wertheimer's point objects. And yet, in terms of the relationship between the larger-non-organization and its individual parts of the situation, these are so similar that we hoped to obtain similar results with this new object. In our experiments, we used an object that was 18 cm long and 3 cm high. The distance between the upper and lower halves of the object varied from 0 to 3.5 cm every 0.5 cm. In the first experiment, these objects acted as a background, against which two horizontal lines of approximately the same length were presented, one 1.8 cm higher and the other the same amount lower than the object, and the subjects had to compare their lengths. The exposure time was always 1.5 sec. After 6 comparisons, the object was removed, and the subject had to answer what he saw between the lines. In these responses, words such as, \ hearts>, were very often encountered. The word was mentioned only when objects were presented with a very strong separation in space, and even then only by a few subjects.

The results of 40 subjects, 5 for each interval, were as follows:

Gap (in cm) 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 Number of word perceptions 0 0 0 0 1 0 2 1

"Dr. Mary Henl has already conducted experiments of this kind, the results of which have not been published. She found that a large organization dominates even when the word and its mirror image are clearly separated in space. Previous experiments have led us to assume that when the subjects will see such an object for the first time, and then separate inscriptions with a gradually increasing separation, then the already established attitude will prevent the awareness and recognition of the word, even when the gap becomes very large. Our subjects were college students.

158 Only 4 out of 40 subjects noticed that they were presented with a well-known word, although in some groups the gap between this word and its mirror image was very large (even with gaps of 3 and 3.5 cm, only three out of 10 subjects perceived the word). Then we conducted an experiment in terms of drawing attention to such objects. The objective conditions, including the time of presentation, were the same. The horizontal lines were also left in place. And again, with each interval, 5 subjects worked. Before presenting the object, the subjects were instructed to describe what they would see while the object had not yet been removed by the experimenter. The horizontal lines were not mentioned "in the instructions. The results of 40 subjects, 5 for each interval, were as follows:

Gap (cm) 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 Number of word perceptions 0 1 2 3 4 4 5 5

It is noteworthy that even when the subjects directly direct their attention to objects lying between the lines, the intervals of 0.5 and 1 cm do not lead to stable recognition of the word. Out of every 10 subjects, no more than 3 realize "the presence of a word under such conditions, and only when the distance increases to 3 cm, the word is already perceived by everyone. Since the action of an attitude that prevents the detection of a word is excluded, it remains only to conclude that for some subjects the word is still strongly suppressed by the larger organization even when the gap reaches about 2 cm. On the other hand, the differences between these results and those obtained in the absence of attention to the object are very large. With the same objects already 24 ( and not 4) the subjects recognized the word. Undoubtedly, our subjects noticed the gap between the halves of the object. We often asked the subjects to complete the drawing in accordance with their description. For the most part, these drawings consisted of two separate figures, even when the subjects did not recognize the words, but it was under such circumstances that the figures least of all resembled a word or its mirror image.

^

SATURATION AND ATTENTION

Thus, the conclusions following from the well-known learning experiments found their confirmation in the experiments just described. We now turn to the question of why the action of attention is directed against the tendency of the larger organization to suppress the dismemberment of perception. In trying to answer this question, we must turn to some principles natural sciences... We mean the fact that when open systems receive energy from the outside, the processes within them intensify, and the systems tend to be more fragmented. Our assumption is that the action of attention on visual objects is a special case of this kind of processes. Suppose that in a closed system, inertia is immediately extinguished by friction. Such a system for any transformation of its internal structure pays with a decrease in the energy available for such work. When this energy drops to a minimum, the system will be either in a state of equilibrium or in a stable state. Some physicists draw attention to the fact that in such states the distribution of materials or processes within the system is maximally homogeneous and symmetric. The reason for this, of course, is that the energy that the system spends on its own transformation is closely related to the difference, heterogeneity and asymmetry of materials and processes. A simple example is such a closed system in which only one particular transformation is possible, caused by a single potential difference (understood in a more general sense of the word). In this special case, the potential difference gradually decreases to a minimum, and the corresponding transformation process fades away. This rule applies only to closed systems as a whole. Very often, the processes in individual parts of such systems are carried out in the "opposite direction. This is in full accordance with general rule as long as the increase in energy in one place of the system is accompanied by an even greater drop in it in another, as is always the case in reality. In this case, the part of this system, where the changes are directed towards increasing energy, is a special case systems. In such a part of a whole, or closed system, the energy and intensity of processes can increase, because the rest of the system plays the role of sources from which this special part can draw energy. When the energy within this kind of open system increases, the differences and heterogeneities existing within it are emphasized and can reach their maximum value. In the utmost simple cases an open system of this kind can again be capable of only one transformation. This transformation (and the potential difference contributing to it) will now intensify until reaching its highest value. Some recent statements about open systems have given the impression that the meaning of the term is not always intelligible enough. Authors who think open systems are mystical entities to which they are not applicable

160 laws of physics make a serious mistake. Undoubtedly, the behavior of some open systems is surprising. "But there is no reason to think that this behavior follows principles that are contrary to the principles of physics. It is true, however, that until now physics has paid attention to only a few types of open systems and that, as a consequence, the relationship between behavior some of these systems and the principles of physics have never been clearly articulated.

The most obvious examples of open systems are organisms. They store (or even increase) energy within themselves, absorbing energy from their environment. If the parts of the environment, which thus serve as a source of this energy, are also included in the consideration, we, of course, again "get a closed system, within which the organism forms an open subsystem. In organisms, the absorption of energy from the outside also leads to ascending processes or to their maintenance. at some constant high level. What has now been said about organisms is also applicable to some of their parts, for example, to the visual projection zones of the human brain. Quite apart from the energy supplied by afferent impulses, the visual cortex can "receive energy from others parts of the brain. Such a possibility, "it seems to us, is realized when a person shows interest in the visual field. Since in this case, the selection of objects in the field is sharpened, the differences between in different parts this field is emphasized, and so on. These changes again acquire the already well-known direction of development within an open system, for which energy is drawn from the outside. It is not necessary that the entire visual field as a whole be subjected to such an action. What we call it can be directed to a specific part of the visual field. Attention, in this "way," binds other parts of the nervous system (as yet unknown) to these kinds of visual objects, and) by doing this, it seems to us, increases the discussed level of energy. As local differences increase again, the clarity of local structures increases. Our experiments with WertheImer point objects can serve as an example of such effects of attention, since in conditions when attention is not drawn to the object, this object is most often perceived as a uniform distribution of spots. Under the influence of attention, the differences in vertical and horizontal intervals become much more effective, and dismemberment appears where until then it was invisible. A similar effect causes attention in relation to the word and its mirror image. While this object is perceived without special attention, the word as a unit of perception remains undetected in the general structure, despite

161 by a significant gap between the two parts. Attention changes this situation in the direction of a more specific organization, in which a word can appear in its known characteristics and thus be recognized. Consequently, attention acts in the direction of dismemberment and from this side is comparable to those physical agents that transfer energy into an open system from the outside. If we are right in the assumption that, under certain CONDITIONS of perceptual attention, the energy of the considered visual processes increases, then there should be an opportunity to demonstrate this fact in psychological experiments.

In accordance with the theory proposed by Köhler and Vallach, the cortical representation of the selected visual object is surrounded by electric currents. These currents will be weaker or stronger depending on the difference in brightness inside and outside; but soon the flow electric charges will certainly weaken due to its own electrotonic action (saturation effect) on the tissue, no matter how high its initial intensity is. We have just assumed that when attention is focused on an object, the underlying cortical processes will intensify, and that. as a consequence of this, the object will appear with greater clarity; but the corresponding amplification of the current will also accelerate its electrotonic effect, as a result, saturation in the critical region will soon become stronger, and the aftereffect of the figure will also be greater than in those regions that represent objects that do not attract the subject's attention. Koehler and Emery (1947) have already cited observations demonstrating this fact. If the object gradually decreases (due to), then it occupies the same place in space for some time. Now, if you place identical objects to the right and left of the anchor point, attention can focus on one of them. When this happens, the object to which the subject directed attention is smaller. If attention now shifts to another object, this object will seem smaller after a while, and so on. Since this phenomenon confirms our considerations, we decided to do the following experiments. Our first attempts were related to the influence of visual attention on the well-known aftereffect of the figure in the third dimension of the visual space. After one object had been exposed for some time to one side of the fixation point, a second (T-object) was presented right in place of the first, which was shifted towards the observer; it seemed closer than the control object presented on the other side of the fixation point at an equal distance from it, and objectively in the same plane. If attention really enhances saturation, its influence should have manifested itself in a situation where first two equal and symmetrically located objects are presented, working for saturation (1-objects), and then, exactly in their place, two others, also equal T-announce ect. Under such objectively equalized experimental conditions, focusing attention on one or another 1-object for a time sufficient for the occurrence of saturation should have led to a displacement of the corresponding T-objects in the direction away from the observer. The experimental technique is described by Köhler and Emery. 1-objects were light gray squares (1.5 inches on a side). They were presented at a distance of 10.5 feet from the subject, who recorded a mark three inches in front of the plane in which the objects were located for 45 seconds. Then two T-objects (squares with a side of 2 inches) were presented three inches in front of the fixation point, and the subject had to compare their position in the third dimension. Some subjects were instructed to focus on the left 1-object, others on the right. Since the distance between the squares and the fixation point was small (about 1.2 inches), it was almost impossible to focus on only one of the squares. In such a situation, apparently, the width of the area to which the subject turned his attention could not be set ad libitum (arbitrarily). We therefore asked the subjects to focus on the fixation point and one of the squares as a pair of objects. It is much more simple task... The subjects were also not required to evaluate immediately, since many of the aftereffects of figures tend to increase to some extent as long as T-objects are perceived. In these experiments, this phenomenon was especially striking. Our subjects were mainly students who did not know about the purpose of the experiments. From the total of subjects (19) 7 were instructed to focus on the right 1-object, the remaining 12 on the left. They were all tested twice. In all cases, before the beginning of the experiments, the difference in depth was checked by concentrating attention only on the fixation point. It was found that its severity was always so high that the actual measurement of the threshold under our conditions was difficult. The results of our experiments are presented in table. 1, where plus denotes estimates that correspond to the expected, zero-cases of the absence of any asymmetry in the localization of T-objects, and minus-scores that are opposite to the expected. and indicate the directions of attention, and the numbers show how many subjects gave the grade belonging to each of the

163 of three categories. The last column indicates the significance levels excluding zero cases. As a result, 31 out of 38 estimates agree with the expected; 4 differ and in 3 cases no differences were noticed. The number of subjects tested with attention to the left side of the field is greater, since it seemed to us advisable to increase their number when it turned out that the observed effect on this side was weaker.

Table 1

The action of attention on satiety: visual probes

Direction Sample + 0 - P Right First. ... ... ... ... 6 1 1 0.016

Second. ... ... ... ... 7 0 0 0.008 Left First. ... ... ... ... 9 1 2 0.032

second. ... ... ... ... 9 1 2 0.032

Table data. 1 show this asymmetry. This phenomenon can be correlated with Hebb's observations. More special attitude can be set to that asymmetry visual perception , which was described by Geffron C, pp. 311-331]. We did not repeat our experiments in a situation where T-objects would move away from the observer. Our form of experiments should be recognized as more demonstrative. Dorothy Dinnerstein and Koehler once conducted experiments in which the effect of self-saturation on objects presented both in front of and behind the plane of the fixation point was investigated. The square was presented either behind or in front of the fixation point, in addition, either to the right or to the left of it. After a saturation period, the position of the saturated square was compared to the position of the square, which now appeared on the other side of the fixation point, but in the same plane of the object. In all observations of this kind, the T-object was perceived closer to the fixation point, regardless of its objective position behind or in front of it. We repeated these experiments with 6 subjects. All their assessments confirmed this rule. This allows one to think that under certain conditions of self-saturation, the depth of three-dimensional visual structures should decrease. That this is really so, it is easy to show by presenting into the stereoscope two slightly disparate projections of a three-dimensional object) to which the corresponding projection is given by means of a fixation mark on one side of them. After a period of saturation, two more projections are added on the other side of the mark, the same with the first so that the three-dimensional position of the old and new objects lends itself to direct comparison. In this case, it is found that the depth of the object that has undergone saturation decreases sharply; it looks flatter than new. We felt that these results needed confirmation. It seems appropriate to investigate this problem in a different situation as well, for example, when the aftereffect, which attention may or may not increase, occurs in a different sensory modality. In subsequent experiments, therefore, the aftereffect of the figure in the area of kinesthesia was studied, where saturation changes the width of the T-object. Will this action be unilaterally intensified (one hand) in the case when, in a situation that is symmetrical in all other respects, the subject's attention is focused on this side? Of course, it is not known whether the same processes underlie attention to kinesthetic sensations as in concentrating attention on a visual object; however) assuming this, we carried out the following experiments. The experimental technique was described by Köhler and Dinnerstein. In the first experiment, two identical 1-objects, 2.5 inches wide, were presented in two hands for 45 seconds. The T-object, which was then perceived by the subject with one hand, was 1.5 inches wide. With the other hand, the subject looked for such a place on the scale, which, as it seemed to him, has the same width as the test object. In the second experiment, the width of the 1-object was 1 inch, the width of the T-object was 1.5 inches. Thus, the aftereffect was created in both experiments, and therefore the corresponding effects caused by one-sided concentration of attention should have had the opposite direction. Moreover, in both experiments, concentration on the side where the T-object was later presented had one effect, while concentration on the other side had a directly opposite effect on the measurement procedure. The scale was always placed to the right of the subject. The subject's eyes were closed. Since subjective equality does not necessarily coincide with objective equality, the first two measurements were taken without prior saturation. In one measurement, the subject's right hand was placed on the scale three steps above the point of objective equality (TOP), with the other, three steps below, the actual sequence was one for the first half of the subjects and the opposite for the second. The mean value of subjective equality (SR) for all 42 subjects was +0.93 of one grade of the scale. This value was significantly different from TOP (p = 0.01). The width of the area perceived by the right hand was underestimated by 28 subjects, overestimated - 9, accurately estimated - 5. In this respect, our results coincide with the results of other researchers.

165 Only a few of our subjects were left-handed. The mean values of SR for subjects who in subsequent experiments focused on the right or left side did not differ significantly from each other. The differential aftereffect, measured after saturation for each subject, referred to his CP as zero. Before saturation began, subjects were instructed to focus on their impressions from one hand. As a pretext, it was said that their results would be compared with the results of other subjects who, during the same experiments, would memorize some material. Table II shows the number of subjects whose ratings coincided with the expected (+), those who did not find a differential effect at all (0), and those who gave ratings that contradict our expectations (-). Of the total number of cases (42), 35 estimates coincided with the hypothesis; there was not a single one that contradicted it, and in the remaining 7 cases it was not possible to establish the direction of the assessment. The significance level was taken for significant samples, which were not included. As it seems to us, there can be no doubt that our assumptions have come true. The predictions turned out to be less successful in the second experiment than in the first.

Table II

Attentional action on satiety: kinesthetic tests

Experiment Direction + 0 - P

I Right. ... ... ... ... ... 10 1 0 0.001

Left. ... ... ... ... ... 10 1 0 0.001

II Right. ... ... ... ... ... 8 2 0 0.004

Left. ... ... ... ... ... 7 3 0 0.008

This was to be expected if we take into account that the choice of the relationship between the values of the 1- and T-objects in the second experiment was less successful. Since the assessments of our subjects did indeed reveal a quantitative deviation from SR, we will add the following table (Table III), which relates more to these deviations, averaged over the results of each group, than to direct real estimates. Under the SEm index, the standard deviations of the means are given. The unit of measurement is one scale stop (1/12 inch).

166

Table III

Effect of Attention on Saturation: Further Evidence on Kinesthesia

Experiment Direction Mean SEm P

meaning

I Right. ... ... ... ... ... +1.27 0.22 0.01

Left. ... ... ... ... ... -1.14 0.21 -0.01

II Right. ... ... ... ... ... -1.10 0.39 0.01

Left. ... ... ... ... ... +1.15 0.39 0.01

Table III confirms the results presented in table. II. When, in this kind of experiment, attention is directed to the kinesthetic sensations in one hand, the corresponding saturation is enhanced. So, 1) on the known objects proposed by Wertheimer, the approximate threshold of dismemberment was determined in conditions of lack of attention to the object and in conditions of attentive perception. The threshold has always been very high, but it was clearly lower on close inspection. The same results were obtained in the case when words were presented at different distances from their mirror images. Under conditions of attentive perception, the word as such was seen and recognized at a much smaller distance from its mirror image; 2) attention enhances the process that underlies the perception of the object. At the same time, saturation is accelerated, and the corresponding aftereffect of the figure is intensified. The aftereffect of the figure both in the third dimension and in the kinesthetic sphere reveals this influence of attention.

LITERATURE

1. Gaffron M. Right and left in pictures. Art Quart., 2. Hcbb D. 0. Organization of behavior, 1949, 49. Kicin G. S. and_Krech D. Cortical conductivity in 1950, 311-331. the brain injured. , 21, 1952, 118-148 4. Cohlcr W. Perceptual organization and learning. , vol. 71, 1958 - 5. Kohler W. and Dinnerstein D. Figural after-effecis in kinesthesis, Miscellana Psychologica Albert Michotte. 1947, 199.

6. Kohler W. and Emery D. A. Figural after-effects in the third dimension nf visual space. , 60, 1947, 159-201.

7. Kohler W. and Wallach H. Figural after-effects.

, 88, 1944, 269-357. S. Krech D. and Calvin A. D. Levels of perceptual organization and cognition. , 48, 1953, 394-400.

167 9. Krechevsky J. An experimenfal investigation of the principle of proximity in the visual perception of the rat. , 22, I \ tJO, 4 \ J i "\\\ 2 \\ J 10. Me Person A. and Renfrew S. Asymetry of perception of size between the right and left hands in normal subjects., 5, 1953, DO -74.11 Wertheimer M. Untersuchungen zur Lehre von der Gestalt

, 4; 1923.301-350. "\\ -" \\ tS.Wertheimer M. Constant errors in the measurement of figural aftereffects. , 67, 1954, 543-546.

168 Merleau-Ponty Maurice (March 14, 1908 - May 3, 1961) - French philosopher of the phenomenological direction, in a number of motives is close to existentialism. He received his philosophical education at Ecole Normal. Prof. at Lyon's high boots, at the Sorbonne and at the College de France (since 1952), where he took the chair of Bergson. Merleau-Ponty was formed as a thinker in conditions of intense interest in G. Marcel and Sartre, spent a lot of time on Hegel. Through A. Gurvich and A. Schütz, he experienced a strong influence of gestalt psychology. From his work on Husserl's unpublished legacy, he came to the conviction that only the development of a version of phenomenology would preserve the deep intuitions of Husserl himself. The idea of the new becomes the central motive in Merleau-Popty's thinking. Based on the analysis of such phenomena of meaning formation. which cannot be interpreted as the result of an arbitrary and conscious determination (such, but Merleau-Ponty, the phenomena of oriented perceptual space, sexual meanings, many symptoms of psychopathology, etc.), he introduces the idea of a special sense-forming principle,. The body itself, according to Merleau-Ponty, is intimately imbued with meaning, not closed on itself as a thing, but, on the contrary, is open to the world.

there is. In this regard, Merleau-Ponty insists on an in-depth interpretation not only as a fundamental structure of consciousness (as Husserl, following F. Brentano, considered it), but also as a deep character of man's relationship to the world in general, his. The body itself is a kind of intentionality,. Existence is carried out in the endless dialogue of the subject with the world. So the world is constituted for the subject as a \ response> to that \ questioning> with which the subject reveals himself in the world. The subject and the world are only two poles of a single phenomenal field. Being a kind of meaning in a phenomenal field, the subject is something more than the most dialogical relations, and yet, he can never become something. it does not exist outside of dialogue. And just as the subject is always situational, so are the meanings in which the world opens up to him. In this regard, Merleau-Ponty points to the specific character of the subject, to the principled and completely irreparable existence: it never escapes the subject at all, somehow it opens up to him, but always indirectly and never to the end, since the subject can never become outside phenomenal field and place it in front of you. The being of man, according to Merleau-Ponty, is the realization and disclosure of his existence; all of it is therefore even on the most high levels(for example, speech and thinking) bears a character that is inaccessible to direct disclosure and requires special procedures of phenomenological analysis, in the understanding of which Merleau-Ponty is close to the late Husserl.

Works:. P., 1942;

... P., 1945; ... P., 1960:. P., 1964,. P., 1964; ... P., 1965:. P., 1968; ... P., 1969; ... P., 1971; ... P .. 1971. Literature: A. De \ V a el-hen s.

3. The last psychological fact of those that confirm the above physiological scheme of motor enhancement of memory is the feeling of active volitional effort accompanying volitional attention. Already above, in the historical review of theories of attention, we saw that volitional effort in the process of attention was the subject of research for many psychologists. Some of them stopped at a simple statement of this fact and declared it an incomprehensible and indecomposable basic fact of consciousness (Reed, D. Stewart, partly Wundt, James, Baldwin), others, more insightful and courageous, indicated those mental circumstances that could be we explain this volitional nature of attention. Two theories deserve special consideration in this respect, since both of them undoubtedly involve fair assumptions. One of these theories explains the volitional or active nature of attention by the fact that this "process is not due to a change in external sensations, but to a process of internal associations and moreover, the associations of ideas with desires and pleasant states, that is, the interestingness of the object of attention. Thus, in the process of volitional attention, a person is determined not from the outside, but, so to speak, from within, from himself, by his own interests (James Mill, Waitz, Lehman, etc.). Another theory rightly points to the source of the feeling of effort, namely, sees it in the muscular movements that constitute, as we have seen, the basis of attention; such an opinion is shared by Brown, Ben, Lews, Zigen and others. We will not enter here into a special analysis of the feeling of volitional effort, since this issue will be studied in detail

142 in our study about<Элементах волевого движения>... Here, it will suffice to note that the effort during attention is undoubtedly due to its motor element, and, thus, this psychological fact is also quite consistent with the above physiological scheme. Even in this chapter, while investigating the phenomena of attention drawn to the peripheral parts of the retina, we will have the opportunity to talk about the nature of the feeling of effort. At the beginning of this chapter, we set ourselves the task of finding out with the help of what process is intense recollection, which constitutes a necessary precedent for volitional attention. Having then expounded the principle of the motor theory of amplification of memories, we indicated that before proceeding to the presentation of a number of facts proving that there is a motor element in almost all memories, we must clarify two assumptions of the motor theory, namely, about the pale and schematic nature of our objective memories of that the strengthening of the motor part of the complex of memories leads to the strengthening of the entire complex. Explanation of the first "assumption led to the study of the doctrine of the mental function of subcortical centers and especially Thalami optici. Explanation of the second assumption led to the establishment of the above physiological scheme and the corresponding psychological facts. Thus, we can only turn now to an explanation of the basic position of the motor theory of attention, namely to an exposition of a number of facts showing that, indeed, in memories there is usually a motor element, that is, ideas about movements. The proof of this position can be difficult only in the sense of embarras de richesse.

143 Rubin Edgar John (b September 1886-1951) - Danish psychologist. He studied at the universities of Copenhagen (1904-1119] and Göttingen (1911-1914), where he worked in the laboratory of G. Müller. In 1916-1918 he was an associate professor, in 1918-1922 he was a lecturer, and from 1922 he was a professor. experimental psychology and director of the psychological laboratory at the University of Copenhagen.His work on the phenomenon of the figure-background Rubin had a significant influence on gestalt psychology (see Woodworth. Experimental psychology. Moscow, 1950).

Compositions:

Literature: E. Rasmus-s en.

E. RUBIN. NON-EXISTENCE OF ATTENTION

The concept of attention is characteristic of naive realism. In psychology, it becomes a source of pseudo-problems. For naive realism, attention means a subjective condition or activity that contributes to the experience of objects with high cognitive value, i.e. so that things are experienced as they are, according to the concepts of naive realism, and in reality. Already because of this evaluative point of view, the concept of attention is unsuitable for psychology. However, attention is an explosive even for the most naive realism, since its basic setting consists in

144 that subjectivity and appearance coincide. If attention is the designation of the subjective conditions of experience, which are limited, then instead of conducting real research, they turn a blind eye to the main theme of psychology, namely, the disclosure and study of these subjective conditions of experience. And since these conditions, which are partially analyzed in the "psychology of the problem", change from case to case, then attention means, although they usually do not think about it, either something very vague, or something heterogeneous, different in different cases. Therefore, not a single definition of attention could satisfy psychologists, while outwardly everything could be explained by attention. Therefore, in reality, attention as an explanatory principle had to disappear whenever research penetrated phenomena and revealed their conditions and facts. Since the term attention does not denote anything definite and concrete, in order to nevertheless put it in correspondence with a certain reality, a frivolous assumption brings to life the fiction of the formal and abstract activity of the soul. The word attention is in most cases unnecessary and harmful. When, for example, a certain Mayer looks at his notebook, then pseudoscientific it can be expressed as follows: "Mayer turned his attention to the notebook." Apparently, they say this not only for the sake of sophistication of expression, but also in order to open the way for a dangerous misunderstanding, As if in our cognitive life there is a certain searchlight that moves here and there on the perceived object. Perceived objects are not available, but they seem to be just waiting for attention as a kind of searchlight to highlight them, they arise only with the assistance of all subjective conditions. The so-called types of attention are only descriptive characteristics of the behavior of various people and have no explanatory power. Instead of simply saying that Meyer is unstable, Meyer is said to be of the unstable type of attention. The talk will talk about what kind of experiences and facts are revealed when two voices are simultaneously exposed.

The results will be given in the form of specific examples in order to show in each individual case how insufficient and non-verbal is the usual way of explaining attention by work.

145 Koffka Kurt (March 18, 1886 - November 22, 1941) - German psychologist, one of the founders of Gestalt psychology. Was born in Berlin. The initial passion for philosophy (Kant, Nietzsche) was replaced by an interest in experimental psychology. after receiving his doctorate from K. Stumpf (1908), Koffka worked as an assistant to O. Külpe and K. Marbe in Würzburg, then - to F. Schumann in Frankfurt (1910). In Frankfurt, Koffka became close with M. Werth the gamer and W. Koehler, together with whom he began to develop the basic principles of gestalt psychology. In 1911-1924. Koffka - assistant professor at the University of Giessen, since 1927 - professor at Smith College in Northampton (USA). Repeated lecture trips to the United States and England in the early 1920s, and especially Koffka's participation in the International Congress of Psychology at Oxford (1923), were crucial for the spread and acceptance of Gestalt psychology. Koffka was the first among Gestalt psychologists to turn to the problems of the child's mental development (1921) and memory (1935). Its fundamental<Принципы

гештальтпсихологии>(1935) in their completeness and skill of presentation still remain an unsurpassed collection of achievements of Gestalt psychology with a subtle and detailed analysis of its main problems. For many years Koffka was the publisher of the magazine

Compositions:<Основы психического развития>... M.-L., 1934;<Самонаблюдение и метод

психологии>... In collection: \ Problems of modern psychology>. L., 1925;<Против мех"

цизма и витализма в сопре" психологии>.

<Психология

ATTENTION

The clear dismemberment turns out to be a function of the field in the whole and its individual characteristics, and not the result of preexisting anatomical conditions. Of the many other highly indicative experiments, I will mention only one in order to reiterate the proposition that the structure of the field as a whole, and thus the clarity of its parts, is determined not by the placement of stimuli or the factor of attention, but by the actual units generated by organization. If a vertical line made up of strokes (Fig. 13) moves away from the fixation point so far, which is still quite clearly perceived, and the observer then focuses his attention on one of the central parts of this line, then as a result it turns out that this part, instead of emphasizing Xia, is reduced and is now seen unclear. Moreover, if you properly select the ratio of the dimensions of the whole

and its parts, this part may disappear altogether, so that the observer will see a gap in the place where this

line. by isolating part of the structural whole, the observer destroys this part. Here we see irrefutable proof that it is the broader whole as some objective fact that determines the visibility of its parts, and not at all the attitude of the observer (...). A beautiful experiment was performed by Gelb (1921). A double black ring with an outer diameter of 36 cm with a black line thickness of 8 mm and a gap of 5 mm was drawn on a large sheet of cardboard. The subject fixes the center of the ring monocularly. Above, another white ring is superimposed, in which there is a gap of about 12Ї, and the object is removed from the subject so that the two arcs visible through the gap merge into one, completely absorbing the white field separating them. If now the upper ring is removed, then you can clearly see a double whole ring with a white gap between the two black circles. Similarly, if, instead of a double black ring, a single color ring is used, and the object is placed at such a distance from the subject so that through the mask superimposed on top, he "sees the already colorless arc of this colored ring, then when the mask is removed,

147 the subject will again see a quite distinctly colored circle (Fig. 14). The opposite effect is observed when we use double straight lines instead of rings and circles. If, at the same distance as in previous experiments, one of the ends of such a line is fixed, then without a mask, the straight lines will merge at a distance of about 10 cm from the fixation point, while a small segment of them will appear double even at a distance of 20 cm. This shows that the degree of organization of the parts of the field depends on the kind of their organization, on their form.Good forms will also be better figures, that is, they will have a clearer division and color than bad forms. lines gain an advantage over the lines as a whole, arises from the concentration of attention on their small areas.Attention, like an attitude (attitude), is a force that originates in the Ego (Ego) and will therefore be considered by us below. But already from of this experiment, we must draw the conclusion that attention, adding energy to one or another part of the field, will increase its dismemberment, unless it is already dismembered already as much as it is generally possible in this case. Since in the case of circles, small parts even lose compared to the whole figure, although they should benefit from increased attention as much as small segments of straight lines, then we must recognize that the internal forces of the organization must be stronger. than the effect created by the energy that attention adds (...). If the empiricist intends to object to our position that the division of the field into a figure and a background is a matter of organization, then he must first of all explain what it is. Since I know of only one attempt at this kind of explanation, resorting to the hypothesis of attention, the inconsistency of which has been repeatedly revealed, I will refrain from discussing it here (see, for example, Koffka, 1922) (... ). We hear a phone call and rush to the phone or, if we are in a pleasant afternoon nap, we feel the urge to answer the phone and growing anger over such anxiety, even if we do not really obey the call. This peculiar "demand" character of the call is obviously the result of experience; it is also obvious that he appeals to certain of our needs. But all this still does not give us a complete picture of what is happening. In relation to this<сигналу>, as well as by

See the corresponding excerpt from Koffka's work below, p. 149. - Ed.

In relation to many others, we must raise the question of why he was singled out. Trying to answer this question, we find that quite often we choose signals only because they are the most suitable to be signals, because in themselves they already carry a certain "demand character" that allows them to be filled with a specific meaning. The unexpectedness, intensity, and intrusiveness of a telephone call are just such characteristics. Attention. These three characteristics were previously listed as "attentional conditions" along with a number of others that we will only mention: certain qualities, such as bitter taste, musk smell, yellow color, have a particularly strong effect on attention. The dispute about the conditions of attention, which a quarter of a century ago was so intense and played a leading role in the psychological drama, has openly lost all interest for psychologists. The reason for this, as it seems to me, lies not so much in the facts that provided material for this dispute, but in the very concept or concepts of attention that left their imprint on it. We see no benefit in parsing these old notions. Instead, we will define attention according to our general system; at the same time, we will receive such a definition of it, "which is in full accordance with the meaning of e of the word in which it is used in everyday language. When we once faced the fact of attention, we said that it represents a force emanating from the ego and directed to the object. This, of course, is what is usually indicated by the word attention when we, for example, say:<пожалуйста, обратите внимание на то,что я говорю>or:<пожалуйста, сосредо-точте внимание на своей проблеме>... To regard attention (as Titchener, 1910) does as simply a quality, attribute, or some dimension of dimension) of objects in a field called clarity is to deprive attention of its main characteristic,

namely, its ego-object interconnectedness. And if we define attention as an ego-object force, then we can consider this to be true in the ratio of not only so-called voluntary, but also involuntary attention. In the first case, the forces come from the Ego; in the second, mainly from the object. This way of looking at attention is naturally not entirely new. He simply did not receive due recognition from those psychologists who wanted to exclude the Ego from their science, and together with the Ego, all psychological dynamics. But when we read Stout's definition (1909):<Внимание есть направленность мысли на тот или нной особенный объект, предпочитаемый другим>, - we learn the same general idea. Indeed, we must assume a certain Ego for stouts-with co and<мысли>.

149 Intensity, surprise, obsession as conditions of attention bring a very definite meaning into our definition. Attention, as a certain force within an integral field, can be awakened not directly by stimulation, but by objects of the field, which, in turn, owe their existence to stimulation. Therefore, we must say that objects that are produced by strong, unexpected and obsessive stimuli, as well as stimuli with special qualities, acquire their special character due to the fact that they act on the ego. If these old statements about the conditions of attention are true, they again indicate that<характер требования>can belong not only to the needs of the Ego, but also to the objects in the field that are produced by this Ego.

LITERATURE

1. Gelb A. Grundfragen der Wahrnehmungs psychologie. Ber. ub. d. VII, Kongr. f. exp. Psych. lena, SS. 114-116.

2.K off k a K. Perception: An Introduction to Gestalt-Theorie.

3. Titchener E. B. A Text-Book of Psychology, N. Y "1910.

4. Stout G.F. Analitic Psychology, vol. 1. L., 1909.

150 Kohler Wolfgang (January 21, 1887 - June II, 1967) - German psychologist, one of the founders of Gestalt psychology. He studied at the universities of Tübingen, Bonn and, finally, Berlin, where he studied physics with M. Planck and psychology with K. Stumpf. He received his doctorate in 1909 for his research in the psychology of hearing. In 1910 he was an assistant, and from 1911 he was a private docent in Frankfurt. Decisive for Köhler, as well as for K, Koffka, was the meeting in Frankfurt with M. Wertheimer. Mutual understanding and cooperation of these psychologists laid the foundation for Gestalt psychology. From 1913 to 1920, Kohler was director of the Tenerife Anthropoid Station in the Canary Islands. Here he carried out his research on the solution of problem situations in chimpanzees, which led him to the field theory of behavior and to an important concept for gestalt psychology.<инсайта>... At the same time, Kehler finishes his composition:

Compositions:<Исследование интеллекта человекообразных

обезьян>... M., 1930;

N.Y. - L., (1929); 3ed. 1959;

Literature: W. C. H. Pren-t i with e.

Kohler's work included in the anthology

V. Koehler and P. Adame

PERCEPTION and ATTENTION

DISTRIBUTION AND ATTENTION

In one of the works devoted to the problem of perceptual organization and learning, we came to the following conclusions.

1. In many situations, learning is no less essential to perceptual dismemberment than a high degree of organization.

2. The high degree of organization exerts strong pressure on the material, which counteracts its dismemberment. Such a strong organization should, apparently, overcome the action of learning and hinder it. However, the pressure of a strong organization can be overcome to a certain extent by the subjects.

3. The threshold for dismemberment within a stronger organization should be high. This threshold will probably be lower, but still quite high in the case when the subject perceives the material, having an attitude that facilitates dismemberment.

These conclusions refer to the perceptual phase of learning. As far as we know, so far [only two studies have been carried out that are directly related to the problem we have touched upon: one, earlier, by Krechevsky and the other, not so long ago, by Krech and Kelvin. The results in both cases do not contradict our conclusions.

Starting with Wertheimer's work on perceptual grouping, a special kind of objects have been used to demonstrate the phenomenon of perceptual organization, one of which is shown in Fig. 15. Such an object is generally perceived as a kind of large unit in the shape of a square. When horizontal (or vertical) rows of dots form within this square, they still remain part of this larger organization. Indeed, the fact that in such objects certain rows of spots form horizontal (or vertical) lines is a demonstration of the phenomenon of dismemberment. This was emphasized by Krech and Kelvii, who used such objects in their experiments. These researchers did not measure the threshold for dismemberment of Wertheimer objects, nevertheless, their results show that it should be very high: even when the distances between the spots in one direction were significantly greater than in the other, the subjects often did not notice this at all. despite the multiple presentation of objects. One could argue that this is due to the fact that the time for presenting objects is very short (0.06 sec). This objection is incorrect. The threshold for dismemberment of such objects is just as high when the exposure time is much longer. We have recently shown this in very simple experiments, where objects were presented for one or even a few seconds. To obtain the magnitude of the dismemberment threshold, we changed the ratio of the distances between the spots horizontally and vertically. Some observations were made when the subject considered the object as a background, which meant distracting attention from the object, others when the subject was persistently demanded to refer to the object as such. In the first series of our experiments, we proposed the first task. The objects were composed of black circles ( 1/8 "in diameter), which were attached to a square of white cardboard (7" side). In one direction (vertical or horizontal), the distance between the circles remained constant, namely 13/16 inches. In the other direction, it decreased from 12/16 to 4/16 inches. To protect objects, they were covered with cellophane on top. The contrast between the circles and the background remained almost unchanged.