Senate of the Russian Empire: history of creation and functions. By decree of Peter I, the Governing Senate was established in Russia 1711 Peter 1 established

Was established Governing Senate- the highest body of state power and legislation, subordinate to the emperor.

Peter's constant absences I from the country prevented him from doing the current affairs of government. During his absence, he entrusted the conduct of business to several trusted persons. 22 February (5 March) 1711 d. these powers were entrusted to a new institution called the Governing Senate.

The Senate exercised full power in the country in the absence of the sovereign and coordinated the work of other state institutions.

The new institution included nine people: Count Ivan Alekseevich Musin-Pushkin, boyar Tikhon Nikitich Streshnev, Prince Pyotr Alekseevich Golitsyn, Prince Mikhail Vladimirovich Dolgoruky, Prince Grigory Andreevich Plemyannikov, Prince Grigory Ivanovich Volkonsky, Krigsalmeister General Mikhail Mikhailovich Samarin, Quartermaster General Vasily Andreevich Apukhtin and Nazariy Petrovich Melnitsky. Anisim Shchukin was appointed chief secretary.

In the early years of its existence, the Senate took care of state revenues and expenditures, was in charge of the attendance of the nobles for service, and was a body of supervision over an extensive bureaucratic apparatus. A few days after the establishment of the Senate on March 5 (16), 1711, the posts of fiscals were introduced in the center and in the regions, who reported on all violations of the laws, bribery, embezzlement and similar actions that were harmful to the state. By the emperor's decree of March 28, 1714, "On the position of fiscals," this service was finalized.

In 1718-1722 gg. The Senate included all the presidents of the colleges. The position of Prosecutor General was introduced, which controlled all the work of the Senate, its apparatus, the office, the adoption and execution of all its sentences, their protest or suspension. The Prosecutor General and Chief Prosecutor of the Senate were subordinate only to the sovereign. The main function of the prosecutor's control was to ensure the observance of law and order. Pavel Ivanovich Yaguzhinsky was appointed the first prosecutor general.

After Peter's death I position of the Senate, its role and functions in the system government controlled gradually changed. The Senate instead of the Governing One became known as the High. In 1741 d. empress Elizaveta Petrovna issued a Decree “On the Restoration of the Power of the Senate in the Board of Internal State Affairs”, but the real significance of the Senate in affairs internal management it was small.

March 5, 2011 marks the 300th anniversary of the establishment of the Senate - supreme body government and legislation Russian Empire.

On March 5 (February 22, old style), 1711, by decree of Peter I, the Governing Senate was established - the highest body of state power and legislation, subordinate to the emperor.

The need to create such a body of power was due to the fact that Peter I often left the country and therefore could not fully deal with the current affairs of government. During his absence, he entrusted the conduct of business to several trusted persons. On March 5 (February 22), 1711, these powers were assigned to the Governing Senate. Initially, it consisted of 9 members and a chief secretary and acted exclusively on behalf of the king and reported only to him.

After the Table of Ranks was adopted (the law on the order public service in the Russian Empire, regulating the ratio of ranks by seniority and the sequence of promotion to ranks), members of the Senate were appointed by the tsar from among civil and military officials of the first three classes.

In the early years of its existence, the Senate dealt with state revenues and expenditures, was in charge of the attendance of the nobles for service, and was a body of supervision over the bureaucratic apparatus. Soon, fiscal positions were introduced in the center and locally, who reported on all violations of laws, bribery, embezzlement and other similar actions. After the creation of collegiums (central bodies of sectoral management), all the heads of collegiums entered the Senate, but this order did not last long, and subsequently the heads of collegiums were not included in the Senate. The Senate oversaw all colleges, except for the foreign one. The post of Prosecutor General was introduced, which controlled all the work of the Senate, its apparatus, the office, the adoption and execution of all its sentences, their appeal or suspension. The Prosecutor General and the Chief Prosecutor of the Senate were subordinate only to the sovereign. The main function of the prosecutor's control was to ensure the observance of law and order.

From 1711 to 1714 the seat of the Senate was Moscow, but sometimes for a while, as a whole or in the person of several senators, he moved to St. Petersburg, which from 1714 became his permanent seat. Since then, the Senate has moved to Moscow only temporarily, in the case of Peter's trips there for a long time. A part of the Senate office remained in Moscow.

In April 1714, a ban was issued to bring complaints to the tsar about the unfair decisions of the Senate, which was an innovation for Russia. Until that time, the sovereign could complain about every institution. This prohibition was repeated in a decree on December 22, 1718, and the death penalty was established for filing a complaint against the Senate.

After the death of Peter I, the position of the Senate, its role and functions in the system of state administration gradually changed. Other supreme state bodies were created, to which the functions of the Senate were transferred. Under Catherine II, the Senate was removed from the main legislative functions of political significance. Formally, the Senate was the highest court, but its activities were greatly influenced by the decisions of the Prosecutor General and the admission of complaints against him (despite the formal ban). Catherine II preferred to entrust the functions of the Senate to her proxies.

In 1802, Alexander I issued a decree on the rights and obligations of the Senate, which, however, had almost no effect on the real state of affairs. The Senate had the formal right to develop bills and subsequently submit them to the emperor, but he did not use this right in practice. After the establishment in the same year of the ministries, the Senate retained the functions of the highest judicial body and supervisory authority, since the main managerial functions remained with the Committee of Ministers (which became the highest executive body).

In 1872, a "Special Presence for the Judgment of State Crimes and Unlawful Communities" was created as part of the Senate - the highest political court in Russia.

By the beginning of the XX century. The Senate finally lost its significance as the highest body of state administration and turned into a body of supervision over the legality of the actions of government officials and institutions and the highest cassation instance for court cases. In 1906, the Supreme Criminal Court was established, which considered the crimes of mainly officials.

In 1917, the Special Presence and the Supreme Criminal Court were abolished.

Decree Soviet power on December 5 (November 22), 1917, the Senate was abolished.

The material was prepared on the basis of information from open sources

Restructuring the system of higher and central government bodies (the Senate, collegiums, state control and supervision bodies). Table of ranks

Peter's state transformations were accompanied by fundamental changes in the sphere top management state. Against the background of the beginning process of formation of an absolute monarchy, the significance of the Boyar Duma is finally falling. At the turn of the XVIII century. it ceases to exist as a permanent institution and is replaced by the first established under it in 1699. near office, meetings of which, which had become permanent since 1708, began to be called Council of Ministers. This new institution, which included the heads of the most important state departments, was initially entrusted by Peter I with the conduct of all state affairs during his numerous "absences".

In 1711, a new supreme body of state power and administration was created, which replaced the Boyar Duma - Government Senate. Established before the departure of Peter I to Prut campaign instead of the abolished Council of Ministers, initially as a temporary government body, whose decrees Peter I ordered to be executed as unquestioningly as the decisions of the tsar himself, the Senate eventually turned into a permanent supreme administrative and control body in the state government.

The composition of the Senate has undergone a number of changes since its inception. At first it consisted of noble persons appointed by the sovereign, who were entrusted with the administration of the state during the absence of the king. Later, from 1718, when the Senate became a permanent institution, its composition changed, all presidents created by that time began to sit in it. colleges (central government bodies that replaced the Moscow orders). However, the disadvantages of this state of affairs soon became apparent. Being the highest administrative body in the state, the Senate was supposed to control the activities of the collegiums, but in reality it could not do this, since it included the presidents of the same collegiums ("now being in them, as they themselves can judge"). By decree of January 22, 1722, the Senate was reformed. The presidents of the collegiums were withdrawn from the Senate, they were replaced by specially appointed persons independent of the collegiums (the right to sit in the Senate was reserved only for the presidents of the Military Collegium, the Collegium of Foreign Affairs and, for a while, the Berg Collegium).

The presence of the Senate met three times a week (Monday, Wednesday, Friday). For the production of cases under the Senate, there was an office, originally headed (before the establishment of the post of Prosecutor General) chief secretary (names of positions and ranks were mostly German). He was helped executor, kept order in the building, sent out and registered decrees of the Senate. At the Senate office were notary actuary(document keeper) registrar and archivist. The same positions were in the boards, they were determined by one "General Regulations".

The Senate also included: Attorney General, Chief of Staff, King of Arms and chief fiscal. The establishment of these positions was of fundamental importance for Peter I. Thus, the general-reketmeister (1720) had to receive all complaints about the incorrect decision of cases in the collegiums and the office of the Senate and, in accordance with them, either force state institutions subordinate to the Senate to a fair resolution of cases, or report about complaints to the Senate. It was also the responsibility of the general-reketmeister to strictly ensure that complaints against lower governing bodies did not go directly to the Senate, bypassing the collegiums. The main duties of the king of arms (1722) were the collection of data and the compilation of nominal service records of the nobility, the inclusion in the genealogical books of noblemen of lower ranks who rose to the rank of non-commissioned officer. He also had to ensure that more than 1/3 of each noble family were not in the civil service (so as not to become scarce with land).

In its main activities, the Government Senate carried out practically the same functions that once belonged to the Boyar Duma. As the highest administrative body in the state, he was in charge of all branches of state administration, supervised the government apparatus and officials at all levels, and performed legislative and executive functions. At the end of the reign of Peter I, the Senate was also assigned judicial functions, which made it the highest judicial authority in the state.

At the same time, the position of the Senate in the system of state administration differed significantly from the role played by the Boyar Duma in the Muscovite State. Unlike the Boyar Duma, which was a class body and shared power with the tsar, the Senate was originally created as a purely bureaucratic institution, all members of which were personally appointed by Peter I and were controlled by him. Not allowing the very thought of the independence of the Senate, Peter I sought to control its activities in every possible way. Initially, the auditor-general (1715) looked after the Senate, later the staff officers of the guard (1721) were appointed for this, who were on duty in the Senate and monitored both the acceleration of the passage of cases in the office of the Senate, and the observance of order in the meetings of this highest state body.

In 1722 a special position was established Prosecutor General The Senate, designed, according to the plan of Peter I, to provide communication between the supreme power and the central government (to be the "eye of the sovereign") and to exercise control over the activities of the Senate. Not trusting the senators and not relying on their conscientiousness in solving matters of national importance, Peter I, by this act, in fact, established a kind of double control ("control over control"), putting the Senate, which was the highest body of control over the administration, in the position of a supervised institution . The prosecutor general personally reported to the tsar on the affairs in the Senate, conveyed to the Senate the will of the supreme power, could stop the decision of the Senate, the office of the Senate was subordinate to him. All decrees of the Senate received force only with his consent, he also monitored the execution of these decrees. All this not only put the Prosecutor General above the Senate, but also made him, in the opinion of many, the first person in the state after the monarch.

In the light of the foregoing, the allegations about vesting the Senate with legislative functions seem disputable. Although initially the Senate had something to do with lawmaking (issued the so-called "general definitions" equated to laws), unlike the former Boyar Duma, it was not a legislative body. Peter I could not allow the existence next to him of an institution endowed with the right to make laws, since he considered himself the only source of legislative power in the state. Becoming emperor (1721) and reorganizing the Senate (1722), he deprived him of any opportunity to engage in legislative activity.

Perhaps one of the most important innovations of the Petrine administrative reform was the creation in Russia of an effective systems of state supervision and control, designed to control the activities of the administration and to observe the state interests. Under Peter I, a new for Russia begins to form prosecution institute. The highest control functions belonged to the Prosecutor General of the Senate. In his submission were other agents of government supervision: chief prosecutors and prosecutors at the collegiums and in the provinces. In parallel with this, an extensive system of secret supervision over the activities of the state administration was created in the form of posts established at all levels of government. fiscals.

The introduction of the institute of fiscals was a reflection of the police nature of the Petrine system of government, became the personification of the government's distrust of the state administration. Already in 1711, the position was introduced under the Senate chief fiscal. In 1714, a special decree was issued on the distribution of fiscals among different levels of government. Under the Senate, there were a chief fiscal and four fiscals, with provincial governments - four fiscals headed by a provincial fiscal, each city - one or two fiscals, each collegium also established the positions of fiscals. Their duty was to secretly check on all violations and abuses of officials, about bribes, embezzlement of the treasury and inform the chief fiscal. whistleblowing encouraged and even rewarded financially (part of the fine imposed on the violator or the bribe-taker went to the fiscal who informed him). Thus, the system of denunciation was elevated to the rank of state policy. Even in the Church, a system of fiscals (inquisitors) was introduced, and priests were obliged by a special royal decree to violate the secrecy of confession and report to the authorities on the confessed if their confession contained one or another "sedition" that threatened the interests of the state.

It has already been said above that the modernization of the state apparatus carried out by Peter I was not distinguished by a systematic and strict sequence. However, on closer examination of the Petrine reformation, it is easy to see that with all this two tasks remained for Peter I always a priority and undeniable. These tasks were: 1) unification government bodies and the entire system of administration; 2) carrying through the entire administration collegiate start, which, together with the system of explicit (prosecutor) and secret (fiscality) control, was, according to the king, to ensure the rule of law in administration.

In 1718-1720. new bodies of central government were established, called colleges. They replaced the old orders and were built according to Western European models. The Swedish collegial structure was taken as the basis, which Peter I considered the most successful and suitable for the conditions of Russia. The creation of collegiums was preceded by a lot of work on the study of European bureaucratic forms and clerical practice. For the organization of new institutions from abroad, experienced practitioners were specially discharged, who were well acquainted with clerical work and the peculiarities of collegiate organization ("skillful in right-handedness"). Swedish prisoners were also invited. As a rule, in each collegium of foreigners, one adviser or assessor, one secretary and one schreiber (clerk) were appointed. At the same time, Peter I sought to appoint only Russian people to the highest leadership positions in the boards (presidents of the boards); foreigners usually did not rise above vice-presidents.

Establishing boards. Peter I proceeds from the idea that “conciliar government in a monarchical state is the best. The advantage of the collegiate system was seen in a more efficient and at the same time objective resolution of affairs (“one head is good, two is better). It was also believed that the collegial structure of state institutions would significantly limit the arbitrariness of senior officials and, no less important, eliminate one of the main vices of the former order system - the widespread spread of bribery and embezzlement.

The collegiums began their activities in 1719. A total of 12 collegiums were created: Foreign Affairs, Military, Admiralty (marine), Staff offices (department of public expenditures), Chamber collegium (department of state revenues), Revision collegium (carried out financial control), Justice Collegium, Manufactory Collegium (industry), Berg Collegium (mining), Komertz Collegium (trade), Patronage and Spiritual Collegia. Formally, the colleges were subordinate to the Senate, which controlled the activities of the colleges and sent them its decrees. With the help of prosecutors appointed in the colleges, who were subordinate to the Prosecutor General of the Senate, the Senate supervised the activities of the presidents of the colleges. However, in reality, there was no clear uniformity in subordination here: not all collegiums were equally subordinate to the Senate (the Military and Admiralty collegiums were much more independent than other collegiums).

Each collegium drew up its own regulations, which determined the range of its actions and duties. The decree of April 28, 1718 decided to draw up regulations for all boards on the basis of the Swedish Charter, applying the latter to the "position of the Russian state." Since 1720, the "General Regulations" were also introduced, which consisted of 156 chapters and was common to all colleges.

Like orders XVII in. boards consisted of common presence and office. The presence consisted of the president, vice president, four (sometimes five) councillors, and four assessors (no more than 13 in total). The president of the collegium was appointed by the king (later the emperor), the vice-president - by the Senate, with subsequent approval by the emperor. The collegiate office was headed by a secretary, who was subordinate to a notary or recorder, actuary, translator and registrar. All other clerical officials were called clerks and copyists and were directly involved in the production of cases by appointment of the secretary. The presence of the collegium gathered in a room specially designated for this purpose, decorated with carpets and good furniture (meetings in a private house are prohibited). No one could go into the "chamber" without a report during the meeting. Extraneous conversations in the presence were also prohibited. Meetings were held every day (excluding holidays and Sundays) from 6 a.m. or 8 a.m. All questions discussed at the meeting of the presence were decided by a majority of votes. At the same time, the rule was strictly observed, according to which, when discussing an issue, opinions were expressed by all members of the presence in turn, starting with the younger ones. The protocol and the decision were signed by all those present.

The introduction of the collegial system significantly simplified (in terms of eliminating the previous confusion in the system of command administration) and made the state apparatus of administration more efficient, gave it some uniformity, clearer competencies. In contrast to the order system, which was based on the territorial-sectoral principle of management, the boards were built according to the functional principle and could not interfere in the field of activity of other boards. However, it cannot be said that Peter I managed to completely overcome the shortcomings of the previous system of government. It was not possible not only to build a strict hierarchy of levels of government (the Senate - collegiums - provinces), but also to avoid mixing the collegial principle with the personal one, which was the basis of the old command system.

Just as in orders, in the newly created collegiums the last word often rested with the ruling persons, in this case the presidents of the collegiums, who, together with the prosecutors assigned to the collegiums to control their activities, replaced the collegial decision-making principle with their intervention by the sole decision-maker. In addition, the boards did not replace all the old orders. Next to them continued to exist ordering institutions, called either offices, or, as before, orders (Secret Office. Medical Office, Preobrazhensky Prikaz, Siberian Prikaz).

In the course of Peter the Great's state transformations, the final formalization of the absolute monarchy in Russia took place. In 1721, Peter I assumed the title of Emperor. In a number of official documents - the Military Regulations, the Spiritual Regulations and others, the autocratic nature of the monarchy was legally fixed, which, as the Spiritual Regulations said, "God himself commands for conscience to obey."

In the general mainstream of the final stage of the process of folding the absolute monarchy in Russia was also carried out by Peter I church government reform, which resulted in the abolition of the patriarchate and the final subordination of the Church to the state. February 14, 1721 was established Holy Governing Synod, replacing the patriarchal power and arranged according to the general type of organization of colleges. The "Spiritual Regulations" prepared for this purpose by Feofan Prokopovich (one of the main ideologists of the Peter's reformation) and edited by the tsar himself directly pointed out the imperfection of the patriarch's sole administration, as well as those political inconveniences that resulted from the exaggeration of the place and role of patriarchal power in the affairs of the state. . The collegiate form of church government was recommended as the most convenient. The Synod formed on this basis consisted of 12 members appointed by the tsar from representatives of the clergy, including the highest (archbishops, bishops, abbots, archimandrites, archpriests). All of them, upon taking office, had to take an oath of allegiance to the emperor. At the head of the Synod was chief prosecutor (1722), appointed to oversee his activities and personally subordinate to the emperor. The posts in the Synod were the same as in the boards: the president, two vice-presidents, four advisers and four assessors.

Under Peter I, in the course of reforming the state apparatus, accompanied by the institutionalization of government, the spread and active implementation of the principles of Western European cameralism, the former traditional model of government was basically rebuilt, in place of which a modern rational model of government is beginning to take shape.

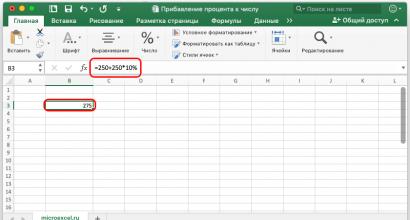

The general result of the administrative reform was the approval new system organization of the civil service and the transition within the framework of the emerging rational bureaucracy to new principles of equipment acquisition government institutions. special role in this process was called to play introduced by Peter I on February 22, 1722. table of ranks, which is considered to be today the first law in Russia on the public service, which determined the procedure for the service of officials and fixed the legal status of persons who were in the public service. Its main significance was that it fundamentally broke with the previous traditions of government, embodied in the local system, and established a new principle of appointment to public office - serviceability principle. At the same time, the central government sought to place officials under the strict control of the state. For this purpose, a fixed salary of state officials was established in accordance with the position held, the use of official position for the purpose of obtaining personal gain ("bribery" and "bribery") was severely punished.

The introduction of the "Table of Ranks" was closely connected with the new personnel policy in the state. Under Peter I, the nobility (from that time called the gentry) became the main class from which personnel were drawn for the state civil service, which was separated from the military service. According to the "Table of Ranks", the nobles, as the most educated stratum of Russian society, received a preferential right to public service. Geli was appointed to a state position by a nobleman, he acquired the rights of the nobility.

Peter I strictly demanded that the nobles serve public service as their direct class duty: all nobles had to serve either in the army, or in the navy, or in public institutions. The entire mass of service nobles was placed under direct subordination to the Senate (previously they were under the jurisdiction of the Discharge Order), which carried out all appointments in the civil service (with the exception of the first five upper classes). Accounting for nobles fit for service and staffing the civil service were entrusted to the Senate king of arms, who was supposed to maintain lists of nobles and provide the Senate with the necessary information on candidates for vacant public positions, strictly monitor that nobles do not shirk service, and also, if possible, organize vocational training officials.

With the introduction of the "Table of Ranks" (Table 8.1), the former division of the nobles into estate groups (Moscow nobles, policemen, boyar children) was destroyed, and a ladder of official class ranks, directly related to military or civil service. The "Table of Ranks" established 14 such class ranks (ranks), giving the right to occupy one or another class position. Occupation of class positions corresponding to ranks from 14 to 5 took place in the order of promotion ( career development) starting from the lowest rank. The highest ranks (from 1 to 5) were assigned at the will of the emperor for special services to the Fatherland and the monarch. In addition to the posts of the state civil service, the status of which was determined by the "Table of Ranks", there was a huge army of lower clerical employees who made up the so-called.

Table 8.1. Petrovskaya "Table of Ranks"

A feature of Peter's "Table of Ranks", which distinguished it from similar acts of European states, was that, firstly, it closely linked the assignment of ranks to the specific service of certain persons (for persons who are not in the public service, class ranks are not provided for), and secondly, the basis for promotion was not the principle of merit, but seniority principle(it was necessary to start the service from the lowest rank and serve in each of the ranks for a specified number of years). In a similar way, Peter I intended to solve two problems at the same time: to force the nobles to enter the public service; to attract people from other classes to the civil service, for whom being in the civil service meant the only opportunity to receive the nobility - first personal, and in the future, hereditary (upon reaching the VIII class rank).

March 5, 2011 marks the 300th anniversary of the establishment of the Senate - the highest body of state power and legislation of the Russian Empire.

On March 5 (February 22, old style), 1711, by decree of Peter I, the Governing Senate was established - the highest body of state power and legislation, subordinate to the emperor.

The need to create such a body of power was due to the fact that Peter I often left the country and therefore could not fully deal with the current affairs of government. During his absence, he entrusted the conduct of business to several trusted persons. On March 5 (February 22), 1711, these powers were assigned to the Governing Senate. Initially, it consisted of 9 members and a chief secretary and acted exclusively on behalf of the king and reported only to him.

After the Table of Ranks was adopted (the law on the order of public service in the Russian Empire, which regulates the ratio of ranks by seniority and the sequence of promotion to ranks), members of the Senate were appointed by the tsar from among civil and military officials of the first three classes.

In the early years of its existence, the Senate dealt with state revenues and expenditures, was in charge of the attendance of the nobles for service, and was a body of supervision over the bureaucratic apparatus. Soon, fiscal positions were introduced in the center and locally, who reported on all violations of laws, bribery, embezzlement and other similar actions. After the creation of collegiums (central bodies of sectoral management), all the heads of collegiums entered the Senate, but this order did not last long, and subsequently the heads of collegiums were not included in the Senate. The Senate oversaw all colleges, except for the foreign one. The post of Prosecutor General was introduced, which controlled all the work of the Senate, its apparatus, the office, the adoption and execution of all its sentences, their appeal or suspension. The Prosecutor General and the Chief Prosecutor of the Senate were subordinate only to the sovereign. The main function of the prosecutor's control was to ensure the observance of law and order.

From 1711 to 1714 the seat of the Senate was Moscow, but sometimes for a while, as a whole or in the person of several senators, he moved to St. Petersburg, which from 1714 became his permanent seat. Since then, the Senate has moved to Moscow only temporarily, in the case of Peter's trips there for a long time. A part of the Senate office remained in Moscow.

In April 1714, a ban was issued to bring complaints to the tsar about the unfair decisions of the Senate, which was an innovation for Russia. Until that time, the sovereign could complain about every institution. This prohibition was repeated in a decree on December 22, 1718, and the death penalty was established for filing a complaint against the Senate.

After the death of Peter I, the position of the Senate, its role and functions in the system of state administration gradually changed. Other supreme state bodies were created, to which the functions of the Senate were transferred. Under Catherine II, the Senate was removed from the main legislative functions of political significance. Formally, the Senate was the highest court, but its activities were greatly influenced by the decisions of the Prosecutor General and the admission of complaints against him (despite the formal ban). Catherine II preferred to entrust the functions of the Senate to her proxies.

In 1802, Alexander I issued a decree on the rights and obligations of the Senate, which, however, had almost no effect on the real state of affairs. The Senate had the formal right to develop bills and subsequently submit them to the emperor, but he did not use this right in practice. After the establishment in the same year of the ministries, the Senate retained the functions of the highest judicial body and supervisory authority, since the main managerial functions remained with the Committee of Ministers (which became the highest executive body).

In 1872, a "Special Presence for the Judgment of State Crimes and Unlawful Communities" was created as part of the Senate - the highest political court in Russia.

By the beginning of the XX century. The Senate finally lost its significance as the highest body of state administration and turned into a body of supervision over the legality of the actions of government officials and institutions and the highest cassation instance in court cases. In 1906, the Supreme Criminal Court was established, which considered the crimes of mainly officials.

In 1917, the Special Presence and the Supreme Criminal Court were abolished.

The Senate was abolished by a decree of the Soviet government of December 5 (November 22), 1917.

The material was prepared on the basis of information from open sources

THE SENATE INSTEAD OF THE BOYAR DUMA

Following the organization of the provinces in 1711, the Senate was established, replacing the Boyar Duma. Aristocratic in composition, the Boyar Duma began to die off from the end of the 17th century: it was reduced in its composition, since the award of duma ranks was no longer carried out, non-duma ranks, persons of humble origin, but enjoyed the confidence of the tsar. The Middle Office, which arose in 1699, became of paramount importance - an institution that exercised administrative and financial control in the state. The nearest chancellery soon became the seat of meetings of the Boyar Duma, renamed the Council of Ministers.

Going on the Prut campaign, Peter established the Senate as a temporary institution "for our regular absences in these wars." All persons and institutions "under cruel punishment or death" are ordered to unquestioningly carry out the Senate decrees. The Senate turned into a permanent institution with very broad rights: it controlled justice, managed spending and tax collection, "because money is the artery of war", was in charge of trade, and the functions of the Discharge Order were transferred to it.

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SENATE

The features learned under Peter by the Boyar Duma were also transferred to the government agency that replaced it. The Senate came into being with the character of a temporary commission, such as were separated from the Duma at the time of the tsar's departure, and into which the Duma itself began to turn during Peter's frequent and long absences. Going on a Turkish campaign, Peter issued a short decree on February 22, 1711, which read: "Determined to be for the absence of our Governing Senate for management." Or: "For our regular absences in these wars, a Governing Senate was appointed," as stated in another decree. So, the Senate was established for a time: after all, Peter did not expect to live in eternal absence, like Charles XII. Then, the decree named the newly appointed senators in the number of 9 people, very close to the then usual composition of the once populous Boyar Duma […]. By one decree on March 2, 1711, Peter, during his absence, entrusted the Senate with the highest supervision of the court and expenses, concern for multiplying income and a number of special instructions for recruiting young nobles and boyar people into the officer reserve, for examining government goods, for bills and trade , and by another decree he determined the power and responsibility of the Senate: all persons and institutions are obliged to obey him, as the sovereign himself, under pain death penalty for disobedience; no one can even declare the unjust orders of the Senate until the return of the sovereign, to whom he gives an account of his actions. In 1717, reprimanding the Senate from abroad for unrest in government, “what is impossible for me to see at such a distance and during this difficult war,” Peter inspired the senators to strictly watch everything, “you have nothing else to do, just one thing government, which if you act imprudently, then before God, and then you will not escape the court here.” Peter sometimes called senators from Moscow to his place of temporary residence, to Revel, Petersburg, with all the statements for the report, "what was done according to these decrees and what was not completed and why." No legislative functions of the old Boyar Duma are visible in the initial competence of the Senate: like the council of ministers, the Senate is not state council under the sovereign, and the highest administrative and responsible institution for current affairs of government and for the execution of special assignments of the absent sovereign, the council, which met "instead of the presence of his majesty himself." The course of the war and foreign policy were not subject to his conduct. The Senate inherited two auxiliary institutions from the council: the Punishment Chamber, as a special judicial department, and the Near Chancellery, which was attached to the Senate to account and audit income and expenses. But the temporary commission, which is the Senate in 1711, gradually turns into a permanent supreme institution […].

The Council of Ministers met randomly and in a random composition, despite the prescriptions that precisely regulated its clerical work. According to the list of 1705, there were 38 duma people, boyars, roundabout and duma nobles, and at the beginning of 1706, when Charles XII with an unexpected movement from Poland, he cut off messages from the Russian corps near Grodna, when it was necessary to discuss and take decisive measures, under the tsar in Moscow there were only two ministers, thoughtful people: the rest were "on service", in official dispersal. Of the orders in Moscow, only those requiring and spending remained, like the Military, Artillery, Admiralty, Ambassadorial. Financial consumption was concentrated in the capital, and the provincial administration mined it; but in Moscow there was no institution left for the supreme disposal of financial gain and for the supreme supervision of financial consumers, that is, there was no government. Among his military-strategic and diplomatic operations, Peter did not seem to notice that, establishing 8 provinces, he created 8 recruiting and financial offices for recruiting and maintaining regiments in the fight against a dangerous enemy, but left the state without a central internal administration, and himself without direct closest interpreters and conductors of their sovereign will. Such a conductor could not be a ministerial congress in the Near Chancellery without a definite department and a permanent composition, from administrators busy with other matters and obliged to sign the minutes of the meeting in order to reveal their "stupidity". Then Peter needed not a State Duma, deliberative or legislative, but a simple state council of a few smart businessmen who could guess the will, catch the tsar’s obscure thought hidden in the laconic charade of a hastily sketched nominal decree, develop it into an understandable and executable order, and authoritatively look after its execution, - the administration is so powerful that everyone is afraid of it, and so responsible that it itself is afraid of something. Alter ego of the tsar in the eyes of the people, every moment feeling the royal quos ego over him - such is the original idea of the Senate, if only any idea participated in its creation. The Senate had to decide cases unanimously. So that this unanimity would not be squeezed out by someone’s personal pressure, none of Peter’s top employees was introduced into the Senate: neither Menshikov, nor Apraksin, nor Sheremetev, nor Chancellor Golovkin, etc. […] : Samarin was a military treasurer, Prince Grigory Volkonsky was the manager of Tula state-owned factories, Apukhtin was a quartermaster general, etc. Such people understood the military economy, the most important subject of Senate jurisdiction, no worse than any principal, but they could probably steal less than Menshikov, if the senator Prince M. Dolgoruky did not know how to write, then Menshikov was a little ahead of him in this art, with difficulty drawing the letters of his last name. So, the needs of management were created by two conditions, which caused the establishment of the Senate as a temporary commission, and then strengthened its existence and determined its department, composition and significance: this is the breakdown of the old Boyar Duma and the constant absences of the tsar.

Klyuchevsky V.O. Russian history. Full course lectures. M., 2004.

DECREE ON THE OFFICE OF THE SENATE

Section VI. 1. In the Senate it is necessary to say the ranks, which are shown below,

2. to give decrees to the whole state and to decide immediately those sent from us;

3. and others, the like, but specifically: to the ranks of speaking, from the military - to the entire generals, from the state and civil government - to the minister, in the collegium - to the president, in the province and in the province - to the governor, governor and commandant, assessor, chamberlains, rentmaster and zemstvo and court kamisar, also - to collegiate members, including the secretary, and protchim; and in the provinces - by the president, to court courts, obor lantrichters and zemstvo secretaries.

Decree on the position of the Senate on April 27, 1722 // Russian legislation of the X–XX centuries. In 9 vols. T.4. Legislation of the period of formation of absolutism. Rep. ed. A.G. Mankov. M., 1986. http://www.hist.msu.ru/ER/Etext/senat2.htm

SENATE AND NOBILITY

The entire mass of service nobles was put under direct subordination to the Senate instead of the former Order of the Order, and the Senate was in charge of the nobility through a special official "master of arms".

THE MOST IMPORTANT TASK OF THE SENATE

The Senate, as the supreme guardian of justice and the state economy, disposed of unsatisfactory subordinate bodies from the very beginning of its activity. That was in the center a bunch of old and new, Moscow and St. Petersburg, orders, offices, offices, commissions with confused departments and uncertain relationships, sometimes with random origins, and in the regions - 8 governors, who sometimes did not obey the tsar himself, not only the Senate . The Senate consisted of the Reprisal Chamber, inherited from the ministerial council, as its judiciary department, and the Accounts Near Office. in number major responsibilities The Senate was instructed to "collect money possible" and consider state expenditures in order to cancel unnecessary ones, but meanwhile money bills were not sent to him from anywhere, and for a number of years he could not draw up a statement of how much was in the whole state in parish, in expenditure, in the remainder and in the allowance. […] The most important task The Senate, which came out most clearly with Peter at his establishment, consisted in the supreme command and supervision of the entire administration. The near office joined the Senate office for budget accounting. One of the first acts of government equipment of the Senate was the establishment of an organ of active control. By a decree of March 5, 1711, the Senate was instructed to choose a chief fiscal, a smart and kind person, no matter what rank he may be, who should secretly supervise all affairs and check on the wrong court, "also in the collection of the treasury and other things." The Chief Fiscal brought the accused, "of whatever high degree" he was, to account before the Senate, and there he convicted him. Having proved his accusation, the fiscal received half the fine from the convicted person; but even an unproven accusation was forbidden to blame the fiscal, even to be annoyed at him for this "under cruel punishment and the ruin of the whole estate."

Klyuchevsky V.O. Russian history. Full course of lectures. M., 2004.

THE ADMINISTRATION CREATED BY PETER

In a systematic presentation, the administration created by Peter will be presented in this form.

Since 1711, the Senate has been at the head of the entire administration. Around 1700, the old Boyar Duma disappears as a permanent institution and is replaced by the near office of the sovereign, in which, as in the old days, a meeting of the boyars sometimes takes place. During his incessant trips, the conduct of state affairs in Moscow, Peter entrusted not to an institution, but to several trusted persons from the old Duma ranks (Peter did not give these ranks to anyone, but he did not take them away from those who had them) and to persons of new ranks and titles. But in 1711, setting out on the Prut campaign, Peter entrusted the state not to individuals, but to a newly founded institution. That institution is the Senate. Its existence, as Peter himself declared, was caused precisely by the "absences" of the sovereign, and Peter ordered everyone to obey the Senate, as he himself. Thus, the mission of the Senate was initially temporary. It replaced with itself: 1) the old Duma commissions, appointed in order to be in charge of "Moscow" in the absence of the sovereign, and 2) the permanent "Rashny Chamber", which was, as it were, the judicial department of the Boyar Duma. But with the return of Peter to affairs, the Senate was not abolished, but became a permanent institution, in the organization of which, under Peter, three phases are noticed. From 1711 to 1718 the Senate was an assembly of persons specially appointed to be present in it; from 1718 to 1722 the Senate becomes an assembly of presidents of the colleges; Since 1722, the Senate has received a mixed composition, it includes some presidents of the colleges (military, naval, foreign), and at the same time it has senators who are alien to the colleges.

The department of the Senate consisted in control over the administration, in resolving cases that were beyond the competence of the collegiums, and in the general direction of the administrative mechanism. The Senate was thus the highest administrative body in the state. Him, in last years Peter, a judicial function was also assigned: the Senate became the highest judicial instance. As to whether the Senate was inherent in legislative activity, there are different shades of views. Some (Petrovsky "On the Senate in the reign of Peter the Great") believe that the Senate at first had legislative power and sometimes even canceled the decrees of Peter himself. Others (Vladimirsky-Budanov in his critical article "The Establishment of the Governmental Senate") argue that the Senate never had a legislative function. But everyone admits that Peter, by changing the position of the Senate in 1722, deprived him of legislative power; it is clear that Peter could not place assemblies with legislative rights next to him, as the only source of legislative power in the state. Therefore, if the Senate is recognized as having a legislative function, then it should be considered an accidental and exceptional phenomenon.

The difference in ideas about the state significance of it also depends on the difference in ideas about the competence of the Senate. Some consider the Senate unconditionally highest institution in a state that unites and directs the entire administration and does not know any other authority over itself, except for the sovereign (Gradovsky, Petrovsky). Others believe that, while controlling and directing the administration, the Senate itself was subject to control and depended on the "supreme ministers" (that is, persons close to Peter who control the troops, fleet and foreign affairs) and on the prosecutor general, the representative of the sovereign's person in Senate.

Platonov S.F. A complete course of lectures on Russian history. SPb., 2000

http://magister.msk.ru/library/history/platonov/plats005.htm#gl6

V.O. KLYUCHEVSKY’S ASSESSMENT OF PETER’S ADMINISTRATIVE REFORM

“A metropolitan clerk, a passing general, a provincial nobleman threw out the decrees of a formidable reformer and, together with a forest robber, did not worry much about the fact that a semi-powerful Senate and nine, and then ten Swedish-style collegiums with systematically delineated departments operate in the capitals. Impressive legislative façades were used as a cover for general lack of dress. Klyuchevsky V.O. Russian history. Full course of lectures. M., 2004.